Key points

The period of US “exceptionalism” has really been in the last 15 years. Over the longer-term, Australian equity returns are on par with the US.

The trends that drove this US outperformance are fading which will lead to global sharemarket returns being more equal across countries over the longer-term.

These trends are: a structurally weaker US economy, the move from a unipolar to a multi-polar world and the decline in the US dollar.

Diana debates an AI economist

Last week I debated Laura the “robot” at the i3 Asset Allocation Forum, an AI form of a human economist built by the Amplify AI Group. The topic was “The house believes that betting on US exceptionalism is still the superior investment strategy in the 21st century”. I decided to take the bearish view, i.e. that US exceptionalism will not be the superior strategy in the 21st century. Laura took the bullish side. The audience was polled around their view before and after the debate, to see if the original view had shifted. After 45 minutes of debating, I was very happy that I had shifted some of the audience to my perspective that US exceptionalism will not continue this century. There is still a role for human economists after all! In this Econosights, I outline my key arguments for my debate about why US exceptionalism will fade over the course of the 21st century.

Introduction

Investors have become used to the idea of US exceptionalism because since 2010, the US S&P500 has massively outperformed its peers, with the US returning an average of 14% a year compared to Australia at 8.5%/year. But it is actually this most recent period that is the exception. Since the beginning of this century, US equities have returned an average of 8.5%/year, which is the same as Australia and if we included franking credits then Australian investors would fare better.

Looking ahead, here are 3 reasons why US investment returns are not going to outperform its peers in the long-term.

1. The US is structurally weaker and is setting itself up for a period of poorer performance by slowly removing everything that used to make it exceptional.

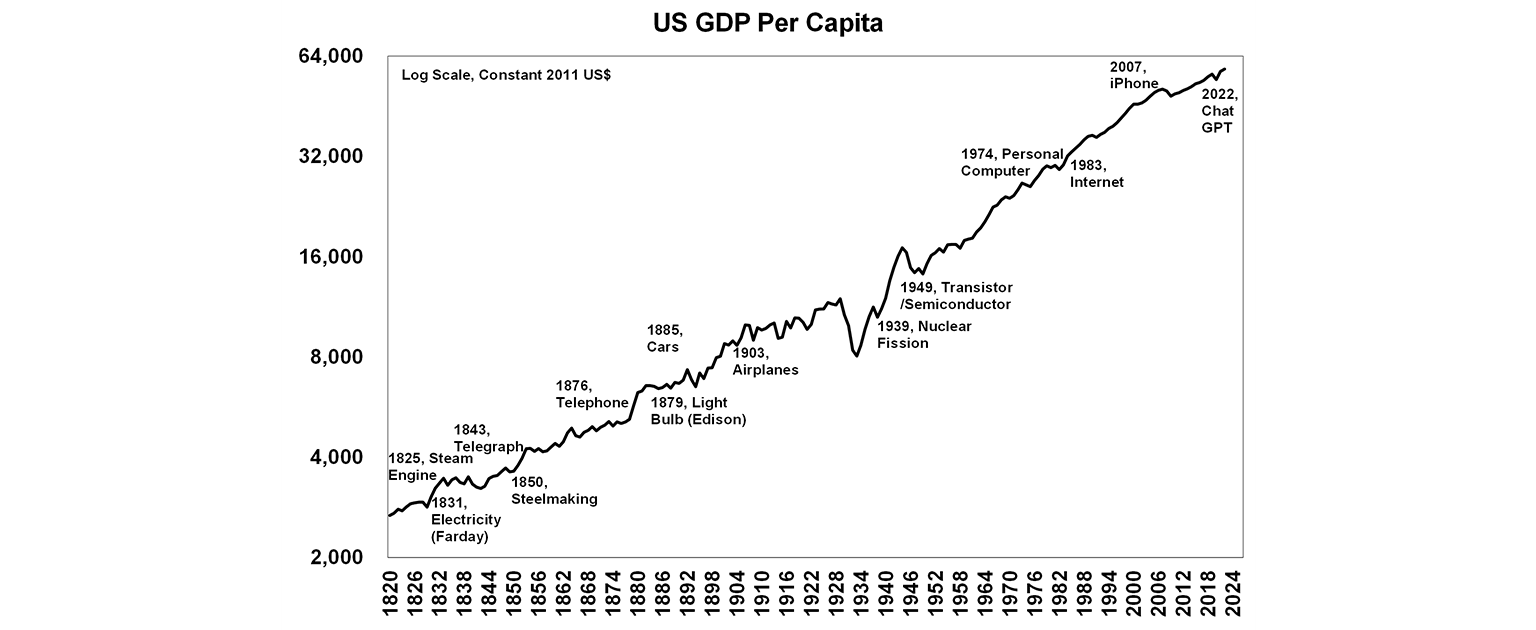

Post-GFC, US economic growth was solid until the short-lived pandemic induced technical recession in 2020. GDP per capita has continued to grow alongside technological advances and economic growth (see the chart below), showing an overall lift in living standards. However, this rise has been unequal. US inequality has worsened, with the Gini coefficient (a measure of the distribution of income or wealth within a population) rising over the last 40 years and above those in Europe and Australia. The top 10% of US income earners now account for 50% of all consumer spending and 70% of consumer wealth. Higher inequality limits economic growth, creates more social tensions, fuels populism and makes the economy less dynamic in the long-term.

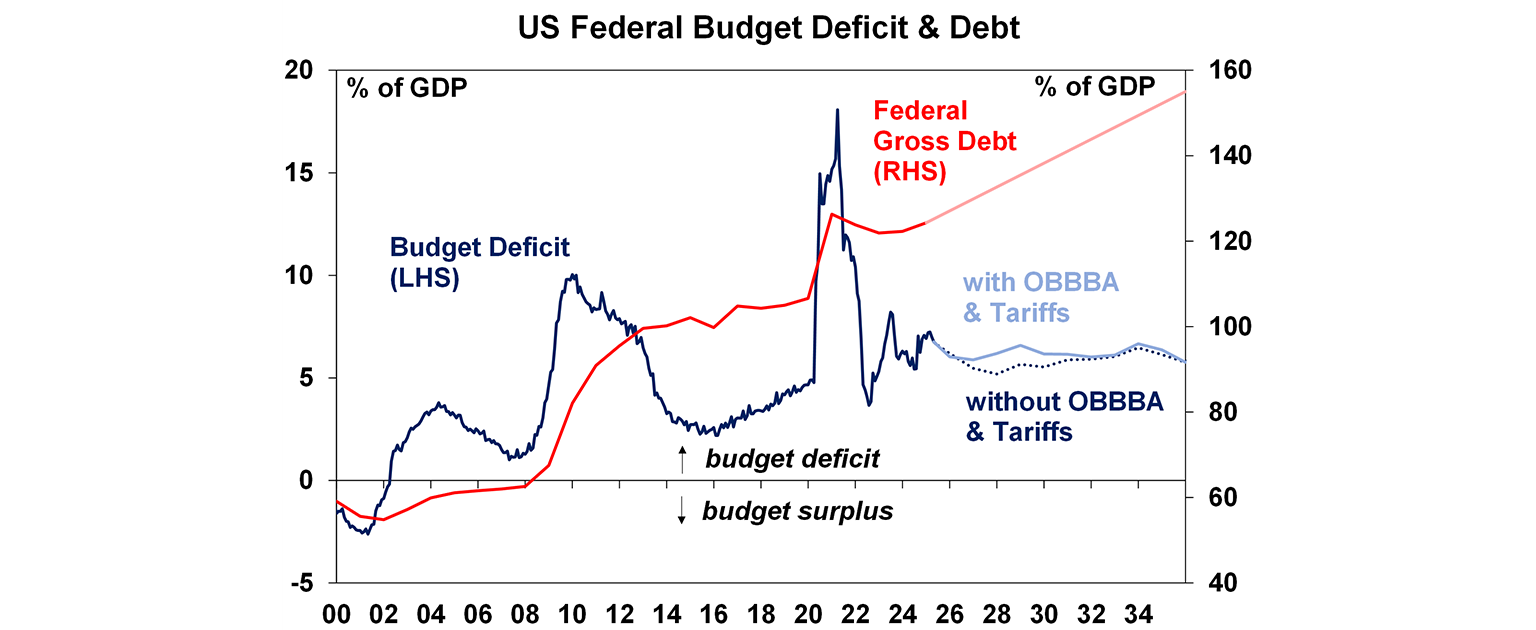

The US budget position has deteriorated. The budget deficit has been rising steadily since the early 2000’s with the current deficit at near $2trillion or over 6% of GDP with no plan to get this into a more sustainable balance. Arguably, the budget situation is just going to get worse with the passage of the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” recently, even accounting for any additional tariff revenue (see the chart below).

While an outright US default remains a very low risk, debt concerns will keep bond yields elevated, increasing the risk premium relative to US equities. And, continuous high budget deficits mean there is less room to create and innovate, as spending is tied to existing programs which may also weigh on productivity growth. In 2025, the US government is expected to spend more on interest payments (at $1tn) than defence and the US Medicare system.

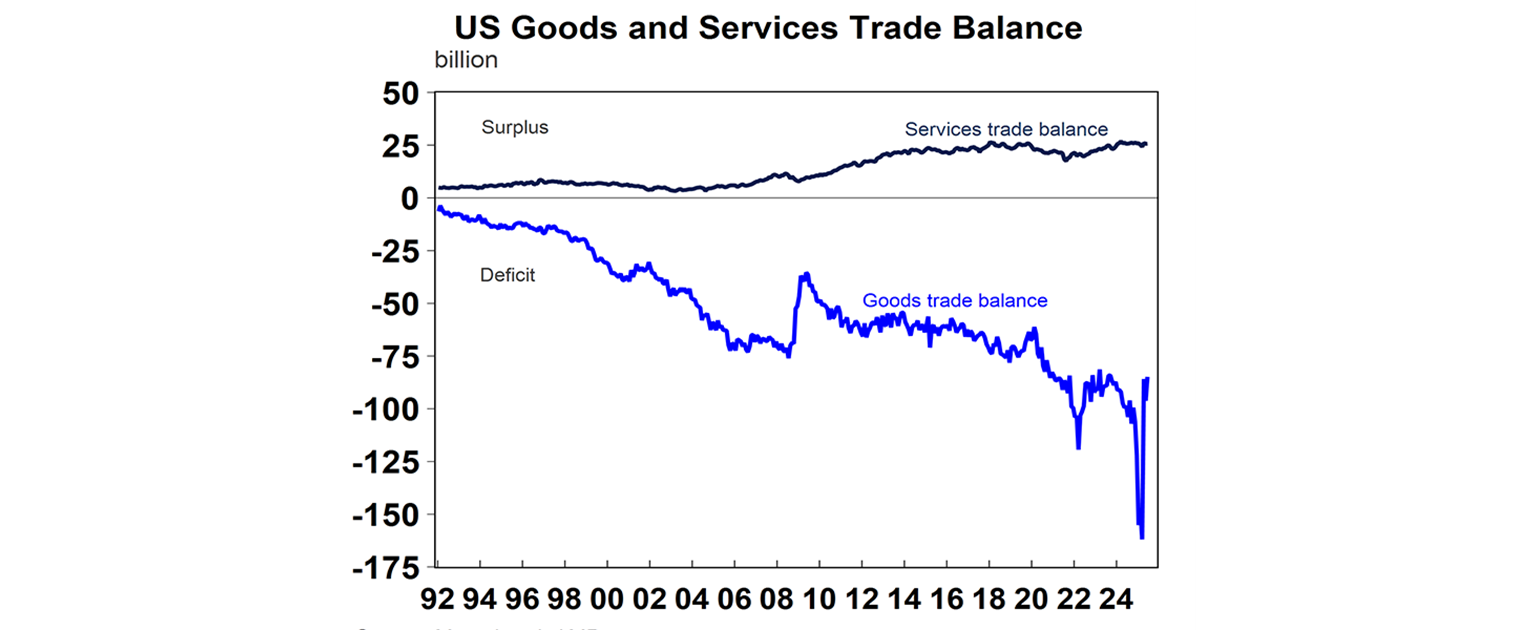

The US had been considered a “brain bank” of the world, seen as a leading attraction for education and research. This is observed in the services trade surplus (which means the US is exporting more services than it is importing) against a deteriorating goods trade deficit (as the US imports more goods than it exports i.e. it is the consumer of the world) – see the chart below. But, this status has been eroded gradually over the past few years. The 2025 Nature Index showed that now 8/10 top global research institutions were in China, with only the US’s Harvard managing to stay in the top 10 list. This trend will only accelerate with President Trump’s recent attacks on academics and research, with cuts to federal research grants to Ivy League colleges, health and science research institutions.

After WWII the US was considered a beacon of hope and prosperity to the world. This is no longer the case as the US has devastated its global influence through weakening alliances on the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, Iran Nuclear Deal, Trans Pacific Partnership, World Health Organisation, North American Free Trade Agreement and NATO. Although I suppose some will argue here that Trump is trying to broker peace around the world and therefore deserves a Nobel Peace Prize!

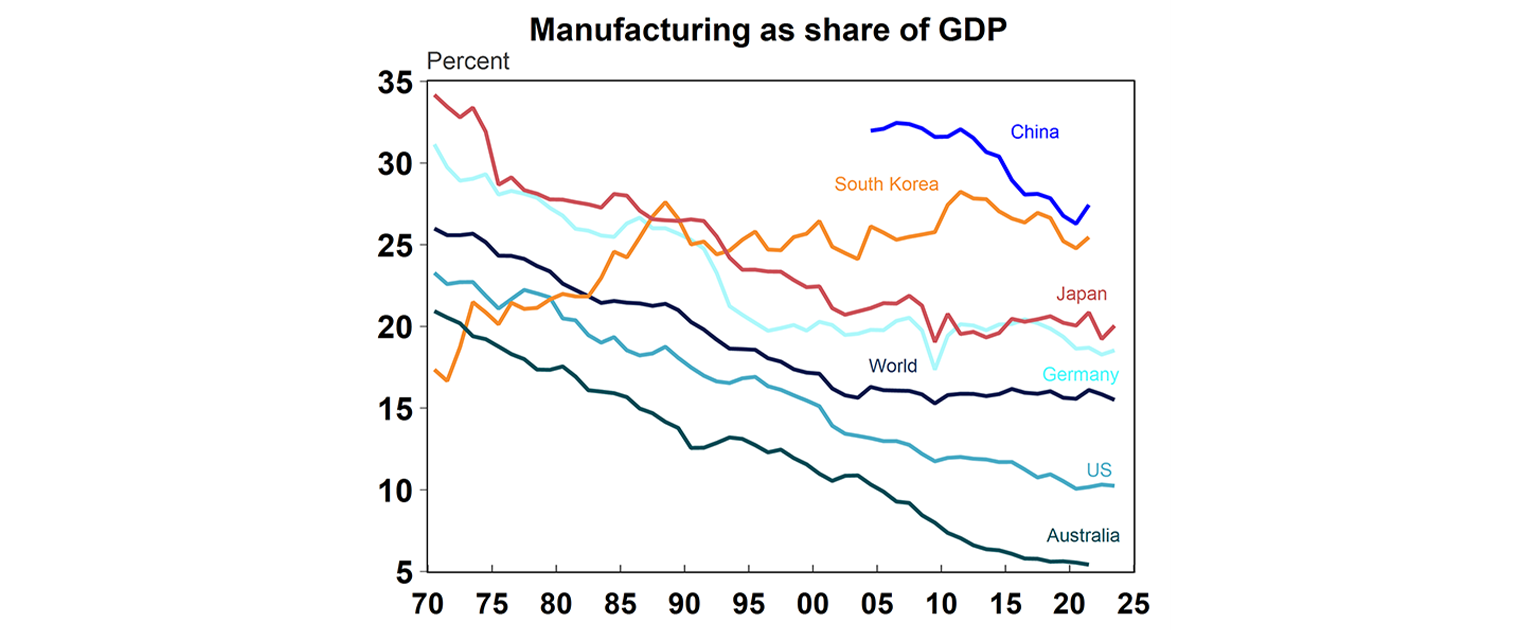

The US is not investing in the future green economy but keeps focussing on the old economy, like its move to go back to trying to stimulate US manufacturing through old-school style tariffs despite manufacturing having been in a structural decline, and now a much smaller share of the economy compared to 50 years ago (see the chart below).

Manufacturing in some areas, like chips is important. But The One Big Beautiful Bill Act eliminated clean energy and electric vehicle credits but increased support for fossil fuels and nuclear.

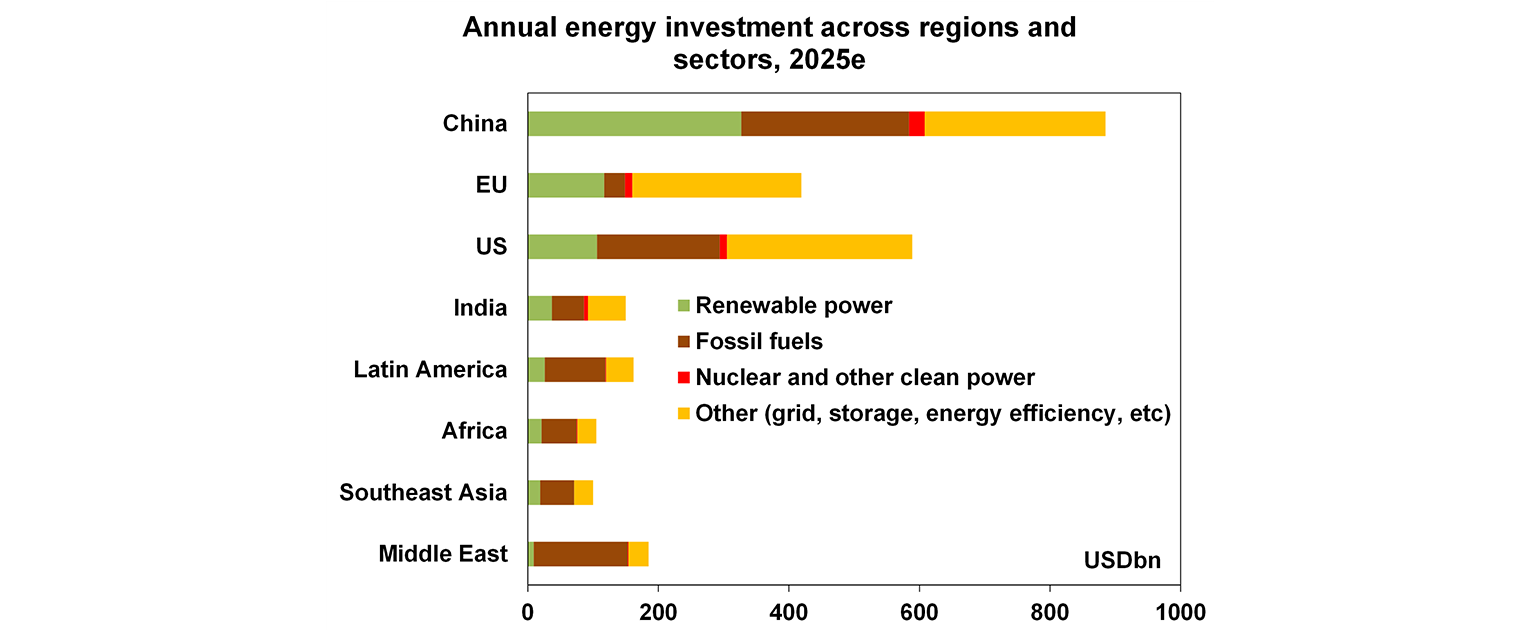

In 2025, China is expected to invest $327bn in renewable energy power, around 3x the US investment for the year. Europe is also making large investments into renewable power (see the chart below).

China has transformed into a tech leader, rather than just a manufacturing hub. I picked up a book from my bookshelf the other week called “Poorly Made in China” published in 2009, about how quality is compromised in the push to expand manufacturing and was surprised at how quickly this dated. China is expected to be the world’s first electro-state. Around 50% of vehicle sales in China are now electric vehicles (compared to 10% in the US and 15% in Australia), in the month of April China installed more solar panels than Australia ever has and half of the world’s wind power capacity is now in China. The lack of US investment into the green economy over multiple years means that energy costs in the US may remain higher for longer, the US will not have a competitive edge on new technologies and exports in the sector and has less global influence in global climate agreements.

2. The US is no longer the world’s hegemon which means we are moving from a unipolar to a multi-polar world

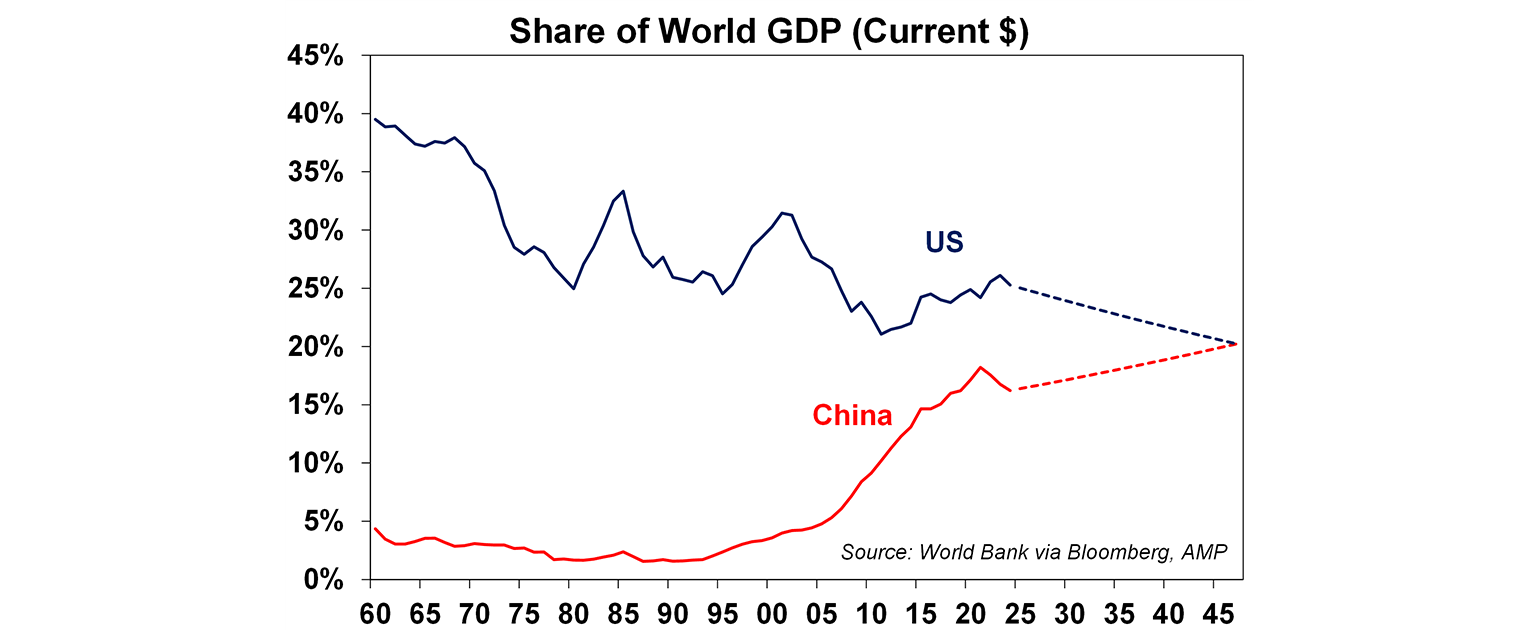

I have written about this before here. China overtook the US as the largest economy in the world in purchasing power parity terms in 2016. The US is now worth 15% of GDP while China is 19% and India is third at 8%. And in current dollar terms, the US and China are expected to be equal shares of the economy in just 20 years (see the chart below).

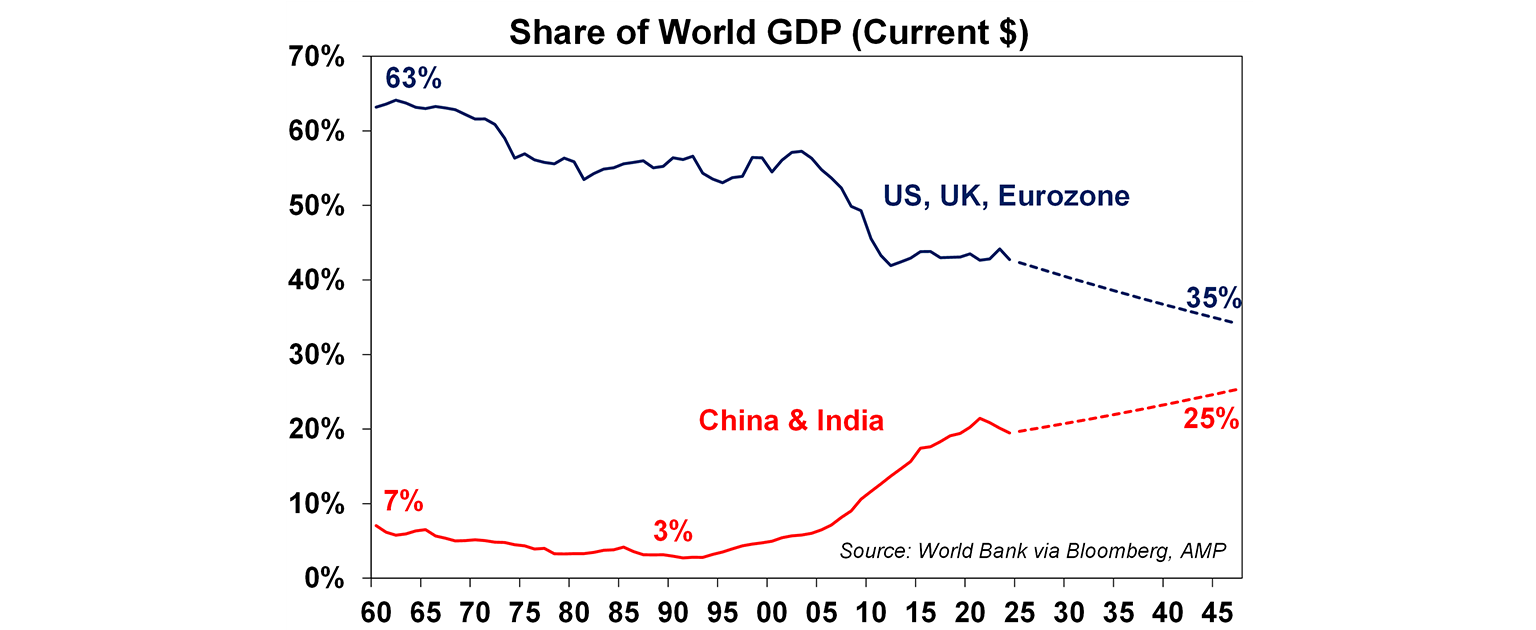

The dominant Western economies of the 20th and 21st centuries of the UK, Europe and the US which accounted for over 60% of global GDP (in current dollar terms) 70 years ago are continuing to lose dominance in the global economy. On current trends the next 20 years will see the UK, Europe and the US fall to 35% of global growth while China and India will lift to 25% and more if we convert it to purchasing power parity terms (see the chart below).

This is occurring because GDP growth, driven by population and productivity in the Western economies is running below that of countries like China and India. China’s productivity growth has been at 4% or above in 2023/24 and between 2011-19 it averaged at 7.8%. India was 6.4% in 2024 and 3.9% in 2023 and 6.2% in 2011-19. US productivity growth is strong for a Western developed economy at just over 1%, but this is still well below China and India.

3. The US dollar safe haven status is seriously under question

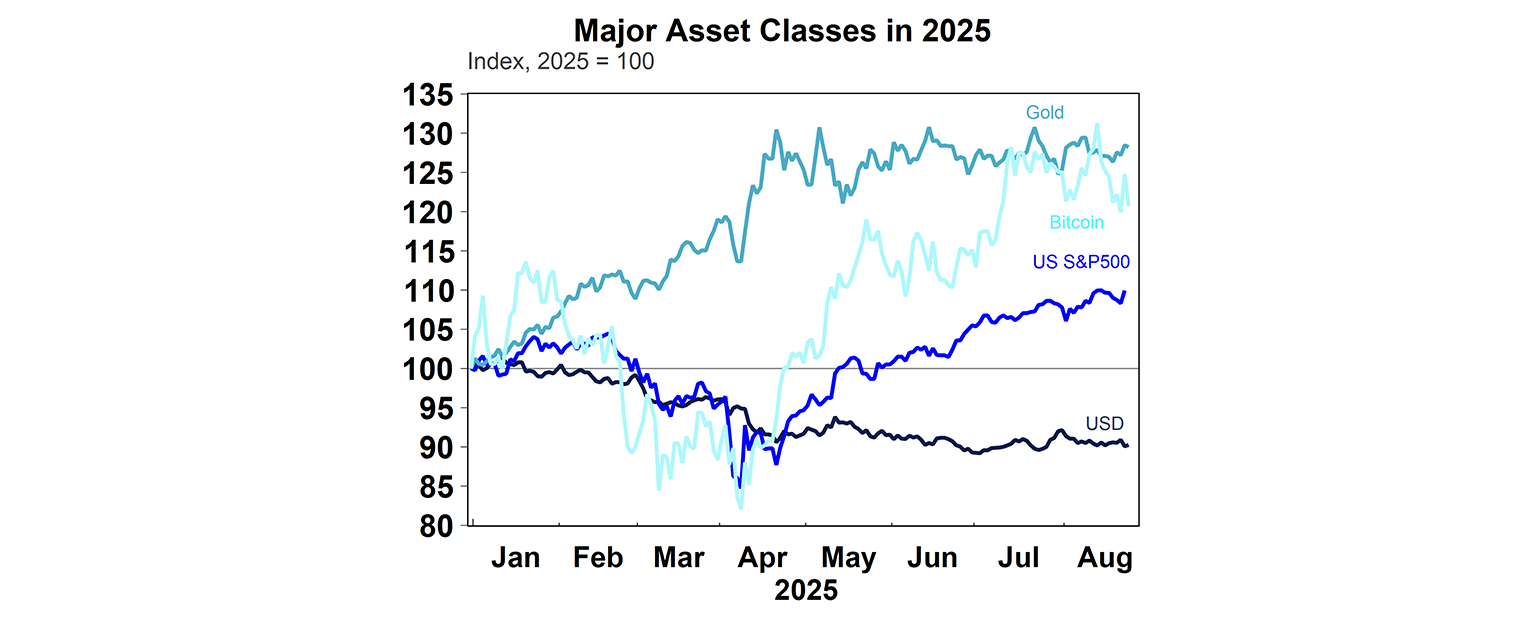

The US dollar has fallen by 10% since the beginning of the year (see the chart below), one of the worst starts to a year for the currency, with the Euro and Yen benefitting from the decline in the $US.

The safe haven status of the $US and demand for the currency is a key pillar of the “US exceptionalism” story. But in an environment where there are question marks about long-term US economic prosperity, a less influential and trustworthy US economy, concern about potential higher taxes on global investors, and more sanctions on some economies, demand for US dollars is likely to struggle. Global official US dollar foreign exchange reserves are already in decline, from around 70% in the early 2000’s to under 60% now. The BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia, Indonesia and Iran) have been talking about de-dollarisation for some time, but this is now gaining more weight because of sanctions already imposed on some countries which limits use of US dollars and technological advancements in payments. The BRICS countries have proposed an alterative currency called “The Unit”, backed by 40% gold and 60% BRICs currencies, available as a digital currency on the blockchain. As the future of money develops and central banks investigate central bank digital currencies, there is a real possibility that the world moves away from relying on US dollars.

Implications for investors

The question around US exceptionalism has received more attention since President Trump started in office (for the second time) earlier this year. While Trump’s brash personality is often used as a reason that US assets will underperform in the long-term, the issues I have described in today’s note supersede Trump and are longer-term structural issues that are weakening the US as a destination for investment. However, some of Trump’s policies are arguably exacerbating some of the structural trends in place and keeping investors nervous (like the potential for the Section 899 tax which has since been scrapped).

In the next few years, other major economies look structurally and cyclically better than they have in recent times. The European economy has struggled in the last 10-15 years, being hindered by high debt levels, poor economic growth, high unemployment, unstable politics, fragmentation risks in the lead up and after Brexit, changing rules in the export environment and more recently high energy costs. However, these issues look to be less of a problem with Europe at the moment, with stronger institutions, better economic growth and signs of more serious fiscal spending and on defence. The Australian economy should also have solid performance. Australia has the potential to be a global leader in critical mineral exports over the long-term. Our sharemarket continues to have solid dividend yields, although earnings growth has been low lately. The Chinese economy has had a tough period post-pandemic but has set itself up well for better growth over the next few years and government policy may turn more government-friendly, making its sharemarket less volatile.

However in the near-term, it is hard for investors to stay away from the US. The US is now 65% of the MSCI all countries weighted index. In 1987 it was 33%. And the Magnificent 7 (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla) are around a third of the US S&P500. And it is still likely that US equities are going to outperform peers in the near-term. Earnings growth in the tech sector remains very high at nearly 30%, while the rest of the index is more around 5%. However, longer-term tech earnings are going to slow as the gains from AI are going to be shared more broadly, not just the initial benefactors who have been the initial investors into AI. It’s also likely that other countries will adopt US AI at a cheaper rate (look at China’s DeepSeek).

In 2025 returns across major sharemarkets have already been close to the US (see the chart below). The end of US exceptionalism does not mean that US sharemarket don’t perform well, it’s just that other markets may offer just as good returns.

Diana Mousina

Deputy Chief Economist, AMP

You may also like

-

The outlook for Australian shares – is the long underperformance over? Australian shares have had a strong start to 2026 with the ASX 200 up 3.3% and flirting with a new record high. The local market has also outperformed US shares which are down 0.1% and global shares which are up 1.6%. However, this could just be noise and follows a significant underperformance against US and global shares since 2009. -

Weekly market update - 20-02-2026 Global share markets mostly rose over the last week. Worries about AI and tech valuations took a breather and the US Supreme Court decision to strike down Trump’s emergency power tariffs with Trump immediately announcing a replacement were seen as having little impact on the US growth outlook but were seen as positive for other countries. -

Econosights - An update on global debt and fiscal policy With the International Monetary Fund releasing their Global Fiscal Monitor recently, AMP's Senior Economist, Diana Mousina provides an update on the global debt situation and recent fiscal policy announcements.

Important information

Any advice and information is provided by AWM Services Pty Ltd ABN 15 139 353 496, AFSL No. 366121 (AWM Services) and is general in nature. It hasn’t taken your financial or personal circumstances into account. Taxation issues are complex. You should seek professional advice before deciding to act on any information in this article.

It’s important to consider your particular circumstances and read the relevant Product Disclosure Statement, Target Market Determination or Terms and Conditions, available from AMP at amp.com.au, or by calling 131 267, before deciding what’s right for you. The super coaching session is a super health check and is provided by AWM Services and is general advice only. It does not consider your personal circumstances.

You can read our Financial Services Guide online for information about our services, including the fees and other benefits that AMP companies and their representatives may receive in relation to products and services provided to you. You can also ask us for a hardcopy. All information on this website is subject to change without notice. AWM Services is part of the AMP group.