Key points

Keeping inflation low and around target is important in terms of maximising living standards in Australia.

We are optimistic that much of the recent rise in inflation will prove temporary.

But some may reflect the economy hitting capacity constraints as a pickup in household and business spending combines with historically high levels of public spending.

The best things governments can do to help lower inflation is reduce the level of spending in the near term and help boost the supply side of the economy in the long term.

Introduction

Much in economics is shades of grey and so subject to some debate. This has certainly been the case around the rebound in inflation in Australia, the RBA’s response and what’s driving it. This note looks at the key issues.

Why did the RBA raise rates?

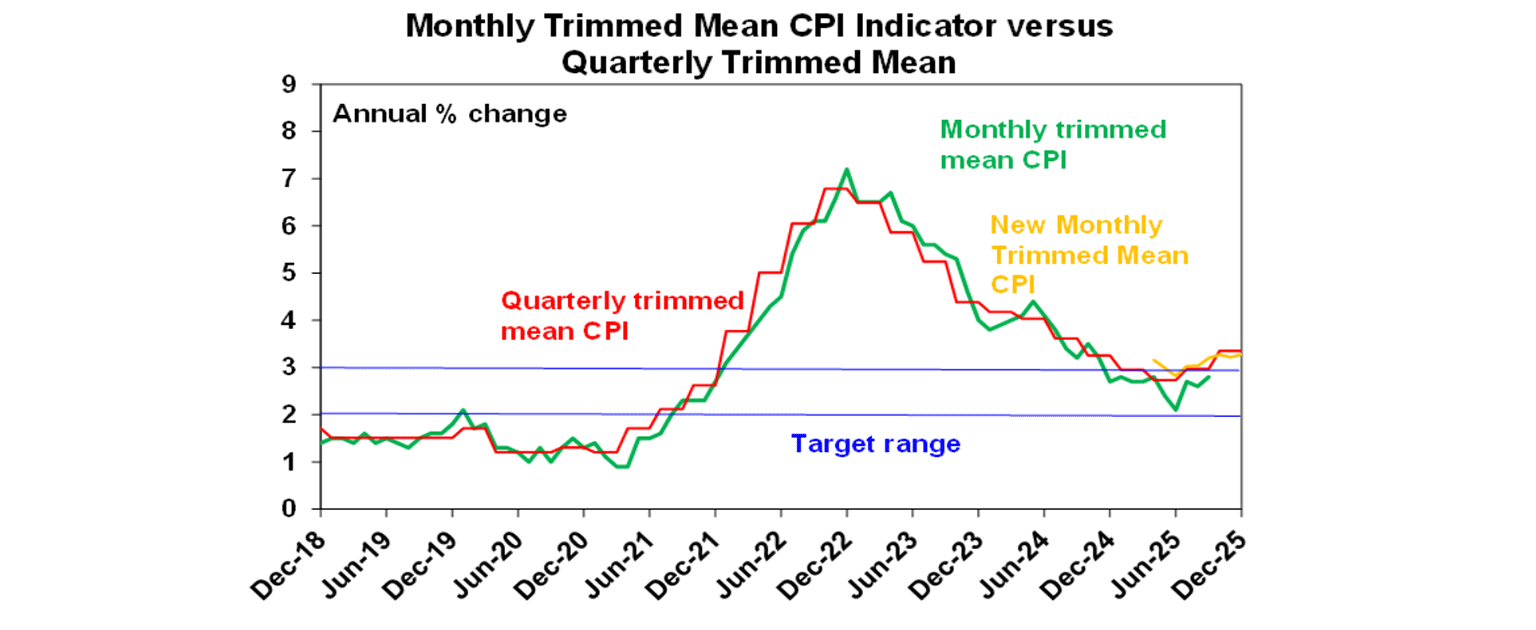

In hiking interest rates by 0.25% to 3.85% the RBA noted that “inflation picked up materially in the second half of 2025” with annual inflation running above the 2-3% target on all key measures. And it said that “while part of the pickup in inflation is assessed to reflect temporary factors…capacity pressures are greater than previously assessed.”

But inflation’s only 3.8%yoy which is not that bad?

True, it’s not the double-digit inflation of the 1970s or even the 8% of 2022. But the RBA is charged with keeping it at 2-3%, and specifically 2.5%. By leaving it running above that level for too long without a response, the RBA worries it will lose credibility in terms of its commitment to the target. And if that happens, community expectations for inflation will rise, making it harder for the RBA to get inflation back down. We are already seeing a bit of that with reports of unions going after wages rises in excess of current inflation and headlines referring to 6% wage claims.

Why the obsession with keeping inflation low?

The problem with high inflation is that it reduces the real value of wages and savings and distorts economic decisions as people try and find ways to protect their real purchasing power rather than focussing on investing productively which leads to lower productivity growth & living standards. This is at the core of the “cost of living crisis” which has seen average prices rise 23% since 2020 but wages rise around 18% resulting in a real fall of 5%. And for mortgage holders, permanently higher inflation will mean a sustained higher level of mortgage rates. The 1970s shows that, once the inflation genie is out of the bottle it’s very hard to get it back in without recession and high unemployment.

Why is the inflation target 2-3%?

Most developed countries concluded they should target low inflation. It was generally concluded that zero inflation would be too extreme - as consumer price indexes tend to overstate inflation because they under allow for quality improvements and as zero inflation would allow little room for real interest rates to go negative if needed - so 2% was agreed as the target, but Australia opted for 2-3%, with the focus now on 2.5%.

Why is it up to the RBA?

Ideally, the Government should be responsible for keeping inflation low, but experience shows that elected politicians are biased to easy money or low rates in order to get re-elected and so have a natural bias to high inflation. As a result after the experience of the 1970s it was concluded that best practice would be for the central bank, i.e. the RBA in Australia, to be charged with meeting the low inflation target and that it do this independent of government, albeit it’s ultimately answerable to government (or Congress in the US) in achieving its low inflation objective. Several central banks have a dual mandate that also includes full employment. This does not mean that government should not help out with fiscal policies and other measures to keep inflation low – see below.

But what if the rise in inflation is just temporary?

Of course, the rise in inflation could owe to temporary factors, e.g. if the pickup in consumer spending, home building and business investment proves temporary. In fact, underlying inflation has been trending down since a spike in July last year and was running below 3% annualised in December and business surveys have not shown a spike in inflation. It was for these reasons we thought the RBA could have waited a bit longer and why we think it may be able to avoid further hikes.

What does the RBA mean by capacity constraints?

That said the RBA is aware of this risk. And its concerns about capacity constraints in the economy are valid. Through last year, economic growth picked up with an acceleration in consumer spending, housing investment and business investment. This combined with high levels of public spending may have taken overall demand in the economy to a point that it bumped up against supply constraints as spare capacity was used up. This would also be consistent with above average levels of capacity utilisation evident in business surveys and ongoing evidence that the jobs market might be tight. When demand is above supply, companies and workers are in a stronger position to raise their prices and wages.

Won’t raising rates just add to the cost of living?

Unfortunately, this is true for those with a mortgage. A few decades ago, mortgage interest costs were included in the Consumer Price Index but were removed as they cause a circularity problem with the RBA hiking rates which then boosts inflation potentially necessitating more rate hikes which can then lead to the RBA going too far. But all the evidence suggests rate hikes – by taking spending power away from a key income sensitive group in the economy – do work in pushing inflation back down, albeit with a lag. We saw this in response to the 2022-23 rate hikes.

But aren’t rate hikes unfair for some groups?

This is also true as mortgage holders are hit hard whereas those who have paid off their mortgage aren’t and may benefit from higher rates on their bank deposits. But again, we know that rate hikes work in slowing inflation as mortgage holders cut spending because the value of household debt is nearly double that of bank deposits and those with a mortgage are far more sensitive to changes in their disposable income than retirees. Issues of equity should be addressed by government.

How can government take pressure off inflation?

Governments can do three things to help reduce inflationary pressure:

First, slow the pace of growth in administered prices as they are up 6% yoy versus private sector prices which are up 2.9% yoy.

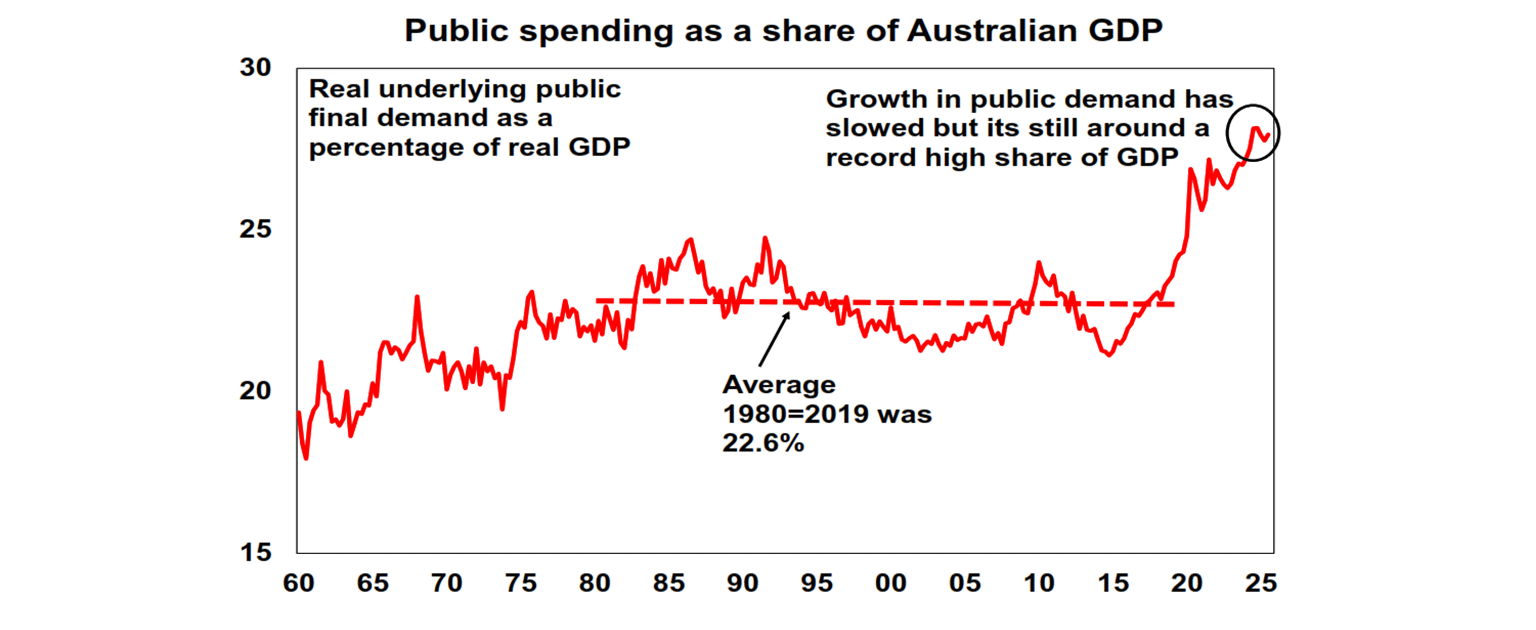

Second, reduce the level of public spending to free up space for the private spending – consumer spending, home building and business investment – to grow more rapidly without pushing the economy up against capacity constraints and causing higher inflation. Some of the debate around this has focussed on the slowdown in public spending growth to 1.3%yoy up to the September quarter as measured in the national accounts at a time when private spending growth picked up more than expected to around 3%yoy, with the conclusion that its private spending causing the problem. But this ignores the fact that public spending is part of demand in the economy and that its level is also very important. And on this front, after many years since late last decade with real growth in excess of 4% pa, public demand in the economy is still around a record 28% of GDP, whereas in the forty years prior to the pandemic it averaged around 22.6%.

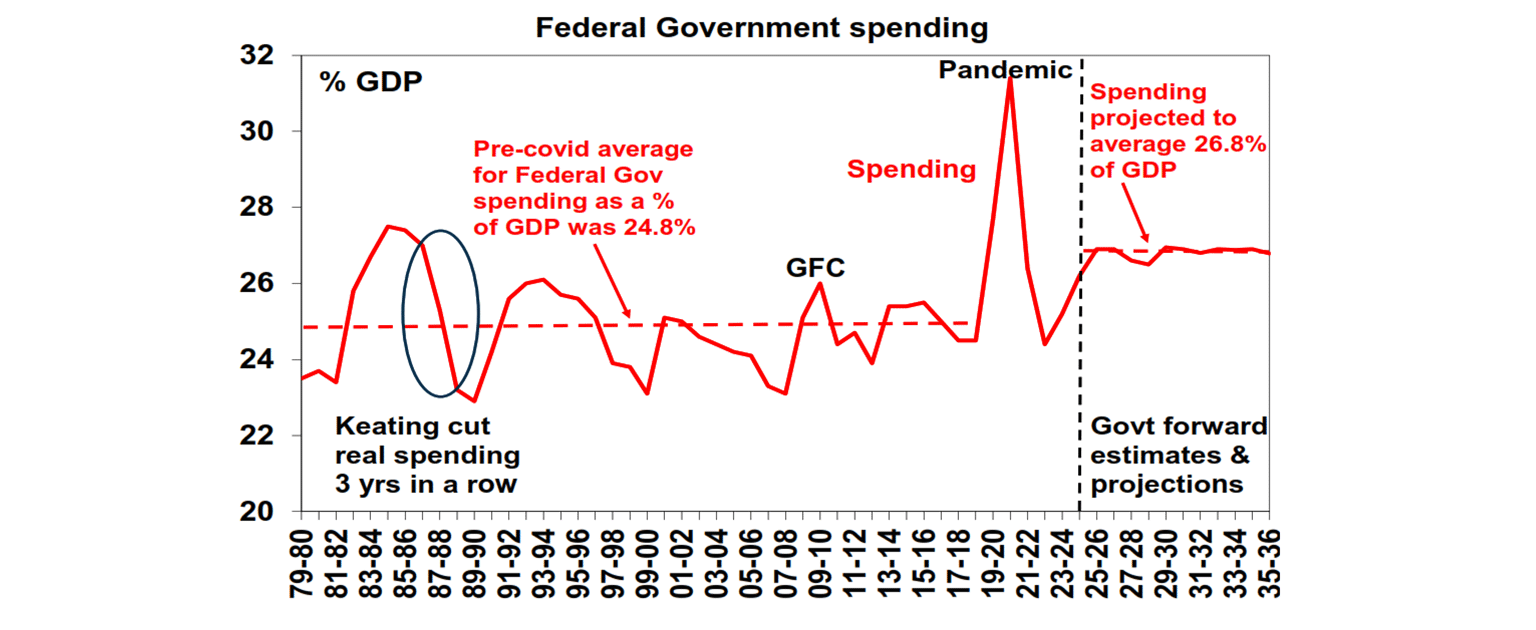

At the Federal level, there is no slowdown in spending growth. The next chart shows Federal Government spending (which includes transfers to the states and households) as a share of GDP. It shows that after big swings around the pandemic, spending as a share of GDP has risen from 24.3% in 2022-23 to a forecast 26.9% this financial year as a result of nominal spending growth of 7.2% in 2023-24, 8% in 2024-25 and 8.2% this financial year. In fact, December budget data shows Federal government spending now growing around 15%yoy. Again, this is seeing public spending settle at a much higher share of the economy than pre-covid which in turn is resulting in capacity pressures as the private sector has sought to spend more.

So, the best thing governments can do to in the near term to help bring down inflation would be to cut the level of government spending which would free up space for private sector demand growth without higher inflation. Failure to do so risks higher for longer inflation and interest rates which leaves all the pressure on consumers to cut spending and on businesses to cut investment.

Finally, implement productivity enhancing reforms like deregulation and tax reform to boost the supply side of the economy to better enable it to meet expanded demand without capacity constraints.

Is the world more inflation prone now?

A productivity boost from AI may rescue us, but there is reason to believe Australia and the world may be more inflation prone now: the ratio of workers to consumers is falling; the rise of populism is leading to protectionism, deglobalisation & irrational government intervention in economies; defence spending rising. So central banks need to be careful.

What’s the relevance of all this for investors?

For investors high inflation is bad as it means: higher interest rates (which makes cash more attractive and other assets like shares relatively less attractive); higher economic volatility and uncertainty; and a reduced quality of earnings as firms tend to understate depreciation when inflation is high. The first two mean rising bond yields which means capital losses for investors in bonds. All three mean shares tend to trade on lower price to earnings multiples when inflation is high, and real growth assets (like property) generally tend to trade on higher income yields. This was seen in the high inflation 1970s when shares struggled. It means that the boost to earnings (or say rents in the case of property) from inflation tends to be offset by a negative valuation effect as investors demand lower PEs/higher yields. So, a sustained period of high and rising inflation can be a problem for bonds, shares and other growth assets. That’s why it’s in investors’ interest that inflation is kept low and stable.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP

You may also like

-

Oliver’s Insights – Oliver's Insights - Gulf War-3 US/Iran war Geopolitical shocks have been a rising feature this year with US “interventions” in various countries – Nigeria, Venezuela, Greenland and now Iran. -

Weekly market update - 27-02-2026 Australian shares are a key beneficiary of the rotation trade helped by the now concluded December half earnings reporting season confirming that listed company profits are rising again. -

The outlook for Australian shares – is the long underperformance over? Australian shares have had a strong start to 2026 with the ASX 200 up 3.3% and flirting with a new record high. The local market has also outperformed US shares which are down 0.1% and global shares which are up 1.6%. However, this could just be noise and follows a significant underperformance against US and global shares since 2009.

Important information

Any advice and information is provided by AWM Services Pty Ltd ABN 15 139 353 496, AFSL No. 366121 (AWM Services) and is general in nature. It hasn’t taken your financial or personal circumstances into account. Taxation issues are complex. You should seek professional advice before deciding to act on any information in this article.

It’s important to consider your particular circumstances and read the relevant Product Disclosure Statement, Target Market Determination or Terms and Conditions, available from AMP at amp.com.au, or by calling 131 267, before deciding what’s right for you. The super coaching session is a super health check and is provided by AWM Services and is general advice only. It does not consider your personal circumstances.

You can read our Financial Services Guide online for information about our services, including the fees and other benefits that AMP companies and their representatives may receive in relation to products and services provided to you. You can also ask us for a hardcopy. All information on this website is subject to change without notice. AWM Services is part of the AMP group.