Key points

Economics provides a range of insights including that: there is no free lunch; prices in free markets are usually best at allocating scarce resources; government policy comes with benefits and costs; productivity underpins living standards; and inflation is mostly a monetary phenomenon.

Unfortunately, these are increasingly being ignored with the rise of populist politicians with simplistic short term policies.

Over the long term this risks a less favourable economic environment – less growth, more inflation and more volatility which could weigh on investment markets.

Introduction

While a casual observation of economists would suggest they are invariably at logger heads this partly reflects the tendency of the media to juxtapose economists with contrasting views on issues like where interest rates, inflation or unemployment are heading. On top of this economists are trained to see all sides of an issue & so are more likely to see things as shades of grey rather than black and white – which is good but many love black and white! As Winston Churchill is said to have said “if you put two economists in a room, you get two opinions...” Or “if you laid all the economists in the world end to end, they’d never reach a conclusion” as often attributed to George Bernard Shaw. But at a fundamental level the economics profession tends to agree on a lot. This note looks at key insights from economics, their relevance today & why they are increasingly ignored.

Ten key economic insights

Note I used AI, and specifically ChatGPT, to help compile this list!

There is no free lunch – the basic economic problem is that human wants are unlimited, but resources are scarce. So we have to learn how to best allocate scarce resources. This means recognising that getting more of something may mean getting less of something else.

Prices guide decisions – prices signal peoples’ preferences and resource scarcity. So if prices are free to move up and down they guide demand and supply decisions without the need for centralised direction. Its often said that “the best solution to high prices is high prices” – because they encourage more producers to supply the item in short supply and potential users to switch to an alternative.

Free markets usually work well in allocating scarce resources, but not all the time - competitive markets tend to allocate resources efficiently to their best uses. But failures occur, eg, where it’s hard to charge for the provision of a good like a lighthouse, where prices may not cover the full cost of supplying a good like the cost of pollution, where a market dominated by a few suppliers or buyers or where key groups do not have access to key information. An example is the failure of markets to capture the potential damage to the atmosphere from carbon emissions – which is the justification for government intervention to put a price or tax on carbon emissions.

Government policy comes with both benefits and costs – for example public spending must be financed and takes resources away from private enterprise which can be more productive, taxes distort economic behaviour and some (like income tax) do so more than others (like a goods and services tax on all spending) and regulation can slow economic activity. For example, public spending in Australia is now around record levels as a share of economic activity & regulations have increased both of which are likely slowing productivity.

Free trade leaves both sides better off – trade between individuals and countries benefits both by allowing specialisation and comparative advantage. For example, Australia exports raw materials to China and imports manufactured goods. Australia has a comparative advantage in mining whereas China has a comparative advantage in manufacturing, allowing Australian consumers to get cheaper manufacturing goods and also freeing up resources for the provision of services where Australia also has a comparative advantage.

Opportunity cost is what really matters - the true cost of any decision is what you give up doing it, ie, the value of the next best alternative — not just the money spent. For example, the true cost of government decision to build a new railway link is not the money it will cost but what that money could have been spent on, eg, a new hospital.

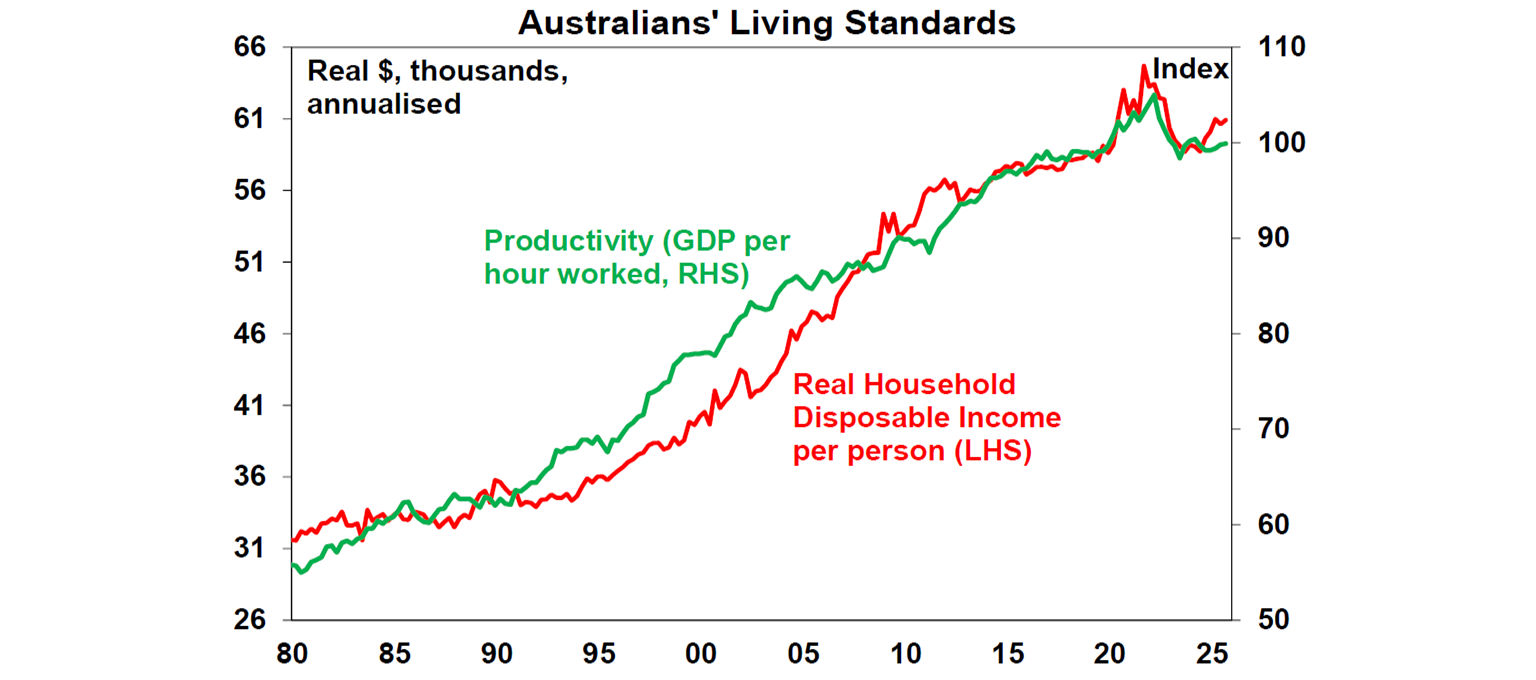

Productivity growth underpins rising living standards - over the long run improvements in real incomes depend on rising productivity or output per hour worked — driven by technology, skills and capital.

8. Inflation is ultimately a monetary phenomenon – while short term inflation can be impacted by supply and demand shocks, sustained inflation requires money supply growth to exceed real output growth.

9. Short run and long run are different – policies that boost demand can raise employment in the short run, but long-run growth depends on supply-side factors like productivity, incentives, and institutions.

10. Expectations matter – what people think affects current decisions and hence outcomes. For example, if workers and businesses expect inflation to stay low then they will be more likely to set wage and price increases at low levels. This is why central banks want to keep inflation expectations at low levels. Likewise, if businesses expect to be whiplashed by erratic announcements from government about tariffs and how to run their business then they will invest and employ less.

Economic rationalism is out of favour

Starting in the 1980s and rolling into the 2000s these lessons were front and centre of economic policy making as the malaise of the 1970s was fresh and led to a focus on sensible economic policy making drawing on many of these insights – free markets, measures to boost competition, smaller government, free trade, monetary policy focussed on keeping inflation down and attempts to anchor expectations at desired levels. But support for economic rationalism is in retreat. There are several reasons for this:

The GFC reduced confidence in free markets. This has been clearly evident in the u turn back towards more state direction in the Chinese economy under President Xi. But also in the increasing intervention in the US economy since President Obama but particularly under Trump.

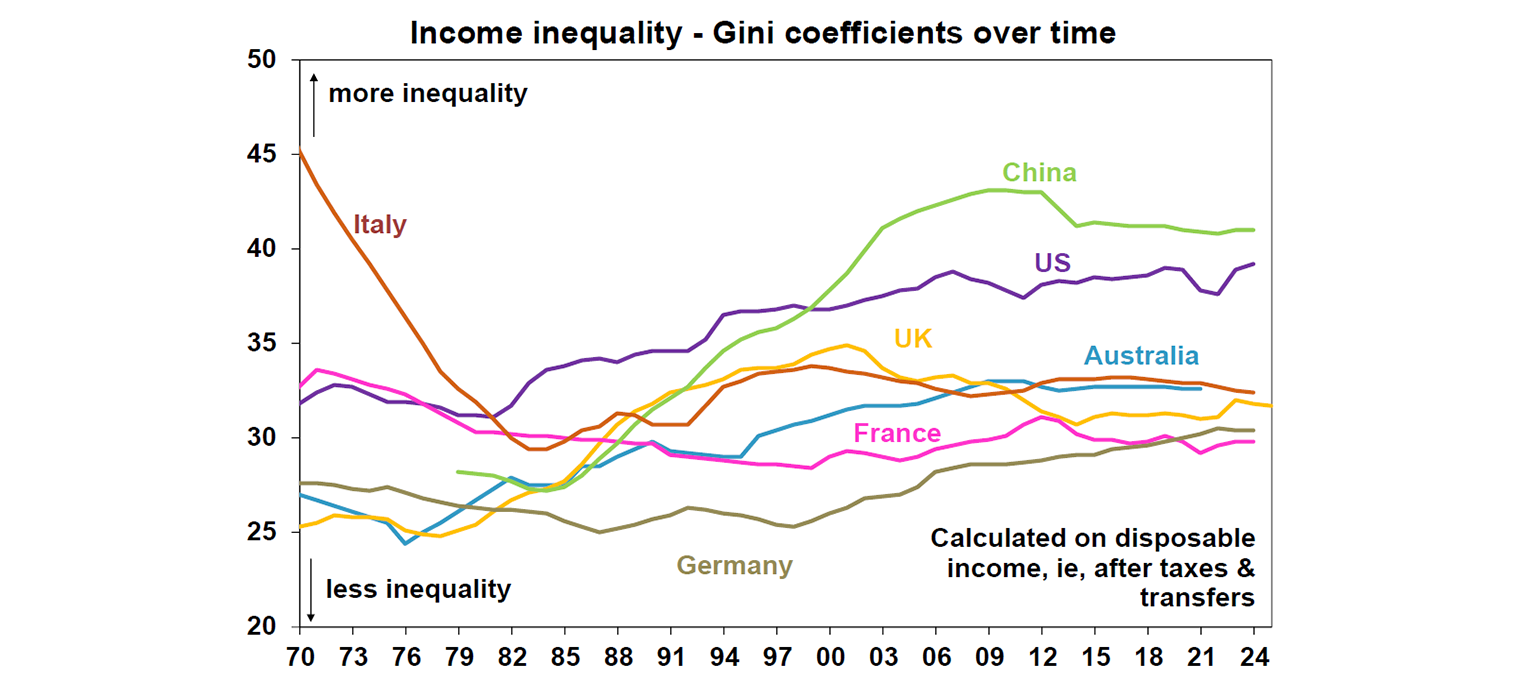

The marginal voter now favours more government intervention in the economy – this likely reflects a combination of rising inequality (notably in the US), perceived cost of living pressures, expectations running ahead of reality (with more going to university and coming out with expectations that they will run things), social media driving and aggravating grievance, the experience in some countries through the pandemic where government backstopped jobs and spending and a dimming of memories of the malaise of the 1970s.

A backlash against high immigration levels has led to a rise in “far-right” nationalist political parties, eg, the National Rally in France, AFD in Germany, the Reform Party in the UK and even Trump in the US.

Economic insights are often counterintuitive – surely government is better at directing the use of scarce resources than free markets? Or they are not what people want to hear – eg, that there is no free lunch.

Policy makers are less inclined to communicate the need for hard choices reflecting the rise of focus groups driving policy and in the face of social media which amplifies grievance and simplistic solutions.

A decline in the study of economics in school and university (in favour of trades like business and finance) may be contributing to increased ignorance of the insights from economics. In Australia economics enrolments in Year 12 are down around 70% on early 1990s levels. The resultant loss of economic literacy may make it harder for people to engage in economic policy debate or resist simplistic populist solutions.

With a loss of faith in the economic system has also come an increasing disregard for the global rules-based order that governed global relations in the post war period for the West and globally since the end of the Cold War. Canadian PM Mark Carney refers to this as a “rupture”. It’s evident in the increasing threat faced by the UN, WTO, the International Court, global efforts to combat climate change, etc. This rules-based order while far from perfect helped reinforce economic rationalist approaches globally, eg in free trade and in the IMF’s assistance to debt ridden countries.

From the age of the economist to the age of the populist

The end result has been a rise in populism. While the far right tends to be dominated by a desire for no or selective immigration, the common features of populists whether left or right are a scepticism of free markets and support for more state direction of and participation in the economy along with protectionism. It’s evident in the US with President Trump where the term “Socialism with American characteristics” is becoming more apt with increasing links between the public and private sectors. It’s evident in the power of the far left and far right in France which is leading to political grid lock. Populism has always been around, but for many years it was on the fringes – but its increasingly taking centre stage. While its impact has been less in Australia it is evident in “Future Made in Australia” policies and the rising tendency for government to prop up struggling steel works and aluminium smelters. Politically, populism has been held at bay in Australia by compulsory voting contributing to a dominance by the centre left ALP and centre right L-NP but this may be coming under threat with the implosion in the Coalition and One Nation now polling ahead of the combined Liberal and National Parties in primary voting intentions.

But populist economic policies tend to fail

The problem is that populist policies offer no sustainable solution to the frustrations people feel and will ultimately make things worse. This is because: by promising more spending and less taxes they ignore budget constraints; by advocating price controls which gives short term relief they worsen things long term by reducing supply (eg, rent controls); they often advocate easy money which invariably leads to high inflation, eg Turkey; they wrongly blame scapegoats like immigrants or institutions like central banks for problems leading to policies that discourage innovation & investment; they go for short term gains (like artificially boosting wages) which leads to long term pain (like unemployment); and their erratic intervention in the economy (eg, raising then cutting tariffs and overriding the rule of law) leads to less investment and employment. And many of Trump’s policies will worsen inequality rather than combat it.

Implications for investors

There are three key implications for investors. First, a less favourable economic outlook – if governments play an increasing role in the economy overriding many of the insights from economics referred to above it’s likely to mean lower productivity over time resulting in slower economic growth and higher inflation than otherwise. In short, lower living standards. Of course, this will take time to show up. In the US at present its being fortuitously masked by the AI boom. Second, the shift to populism and nationalism is leading to increased geopolitical risk which means increased uncertainty. Finally, all of which runs the risk of more constrained and volatile investment returns.

Of course, as an economist I would say the key is to promote the study of economics but of course it’s more complicated! And these things go in cycles with the shift away from economic rationalism to populism likely to have further to go before it’s realised that populism is a dead end.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP

You may also like

-

Oliver’s Insights – US and Iran war QandA Oil and investment markets initially reacted relatively calmly to the US/Israel war with Iran, despite the Strait of Hormuz through which 20-25% of global oil and gas supplies flow through on a daily basis being closed from the get go. -

How much super should I have at my age? See the average super balance for your age group, so you can get an idea of how your super savings compare. -

Econosight International Women's Day 2026 The 8th of March marks International Women’s Day. The gains made to female participation in the labour force and the associated wage boost post-COVID continued into 2025 in Australia, although at a slower pace.

Important information

Any advice and information is provided by AWM Services Pty Ltd ABN 15 139 353 496, AFSL No. 366121 (AWM Services) and is general in nature. It hasn’t taken your financial or personal circumstances into account. Taxation issues are complex. You should seek professional advice before deciding to act on any information in this article.

It’s important to consider your particular circumstances and read the relevant Product Disclosure Statement, Target Market Determination or Terms and Conditions, available from AMP at amp.com.au, or by calling 131 267, before deciding what’s right for you. The super coaching session is a super health check and is provided by AWM Services and is general advice only. It does not consider your personal circumstances.

You can read our Financial Services Guide online for information about our services, including the fees and other benefits that AMP companies and their representatives may receive in relation to products and services provided to you. You can also ask us for a hardcopy. All information on this website is subject to change without notice. AWM Services is part of the AMP group.