Key points

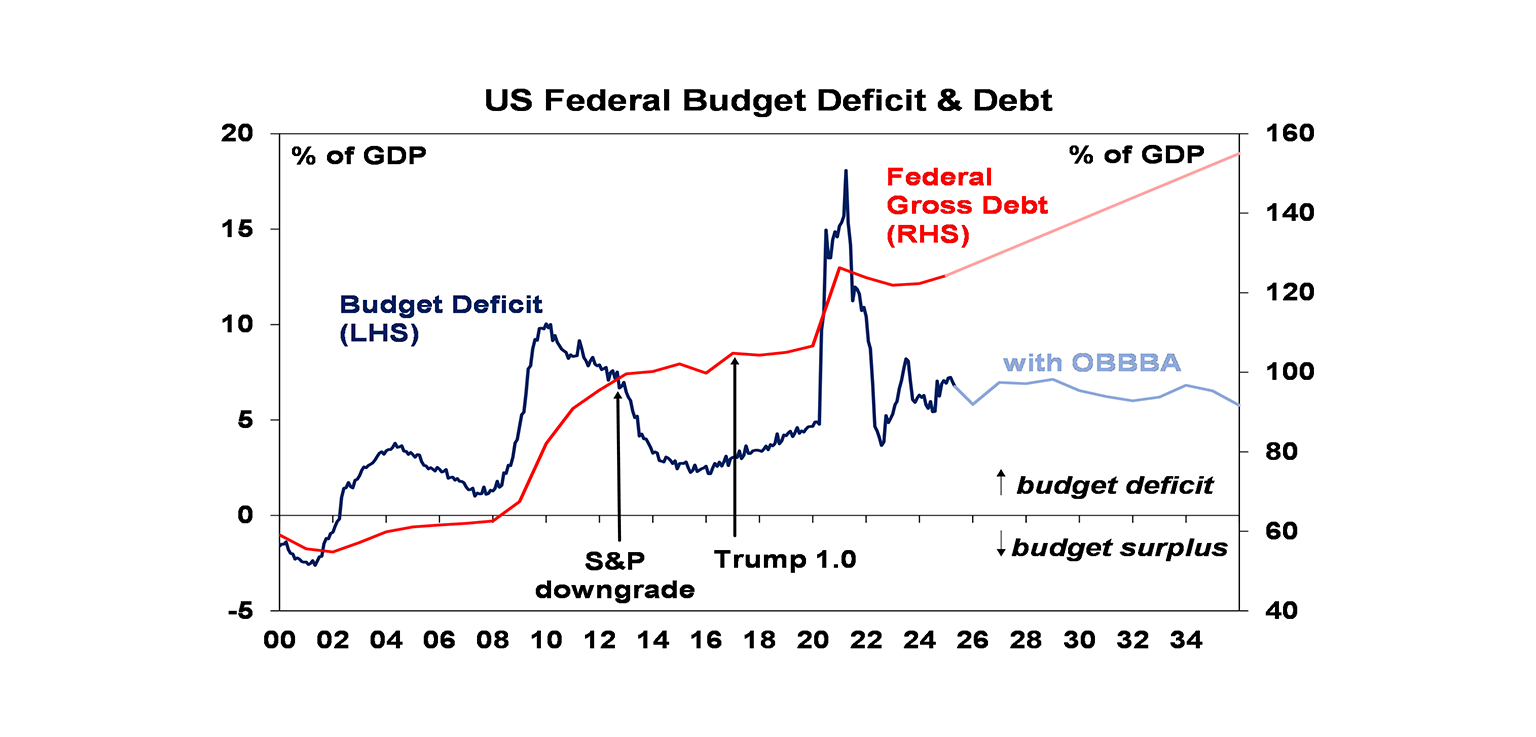

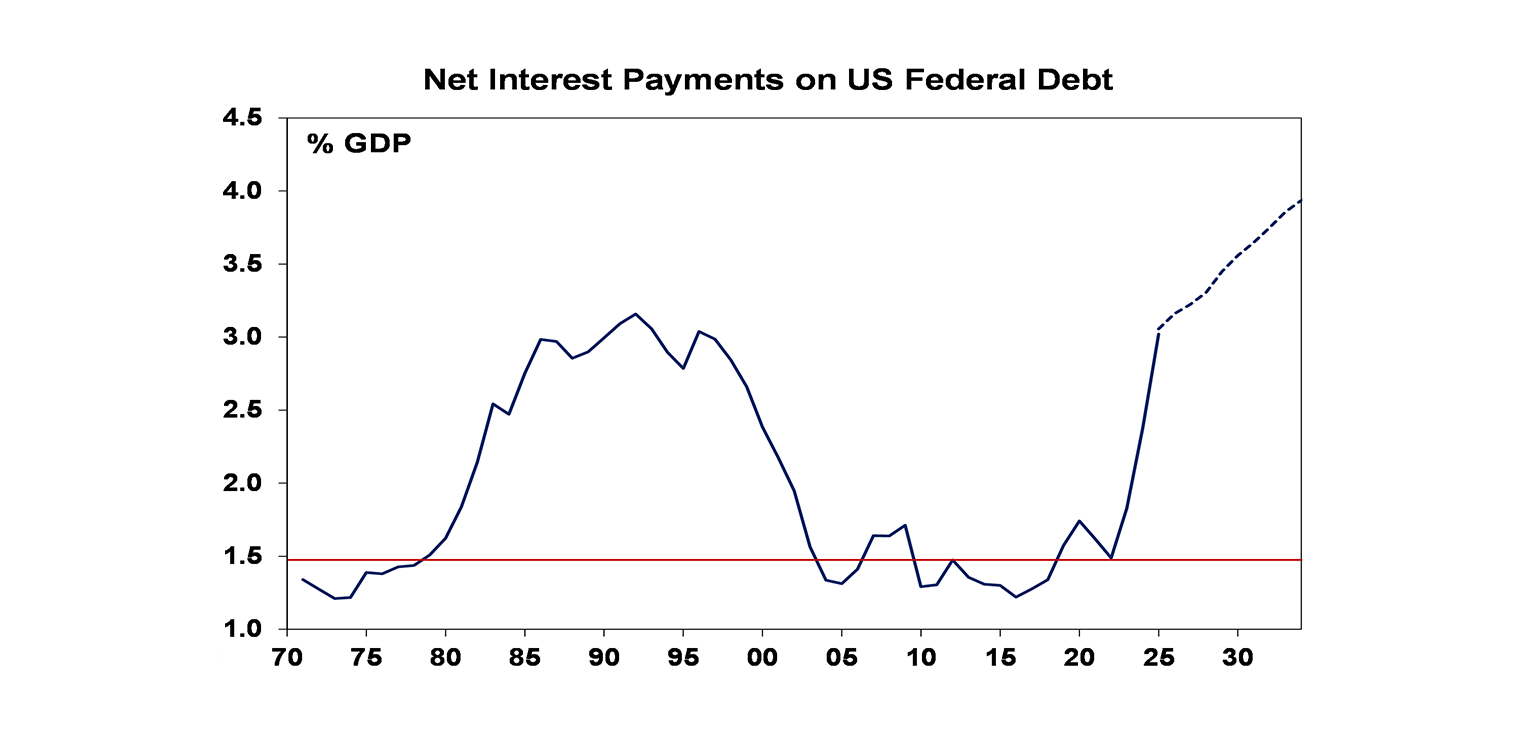

US tax cuts point to ongoing budget deficits around 7% of GDP, a rising trend in already very high public debt and a further rise in already record debt interest payments.

While a full-blown US public debt crisis is unlikely, this along with declining foreign investor confidence in US policy making could mean upwards pressure on US bond yields.

In the near-term shares look like they will break to new highs. But the risk of further tariff and US public debt worries driving another bout of weakness is high.

It’s possible the $US is losing its ‘safe haven’ status. This means the $A may behave a bit less as a shock absorber in a crisis, meaning more pressure on the RBA to cut rates than might normally be the case.

Introduction

President Trump’s tariffs remain a source of ongoing uncertainty. Just in the last two weeks, Trump announced a 25% tariff on smart phones and threatened a 50% tariff on European goods from June, then delayed it until 9th July. The US International Trade Court then ruled that the “Liberation Day” reciprocal tariffs and the Fentanyl tariffs on China, Canada and Mexico were illegal, which saw the Trump Administration appeal the decision through which time the tariffs remain in place. The Administration is now investigating other legal authorities on which to maintain the tariffs in case the appeal fails, and Trump has announced that the tariff on steel and aluminium will double to 50%.

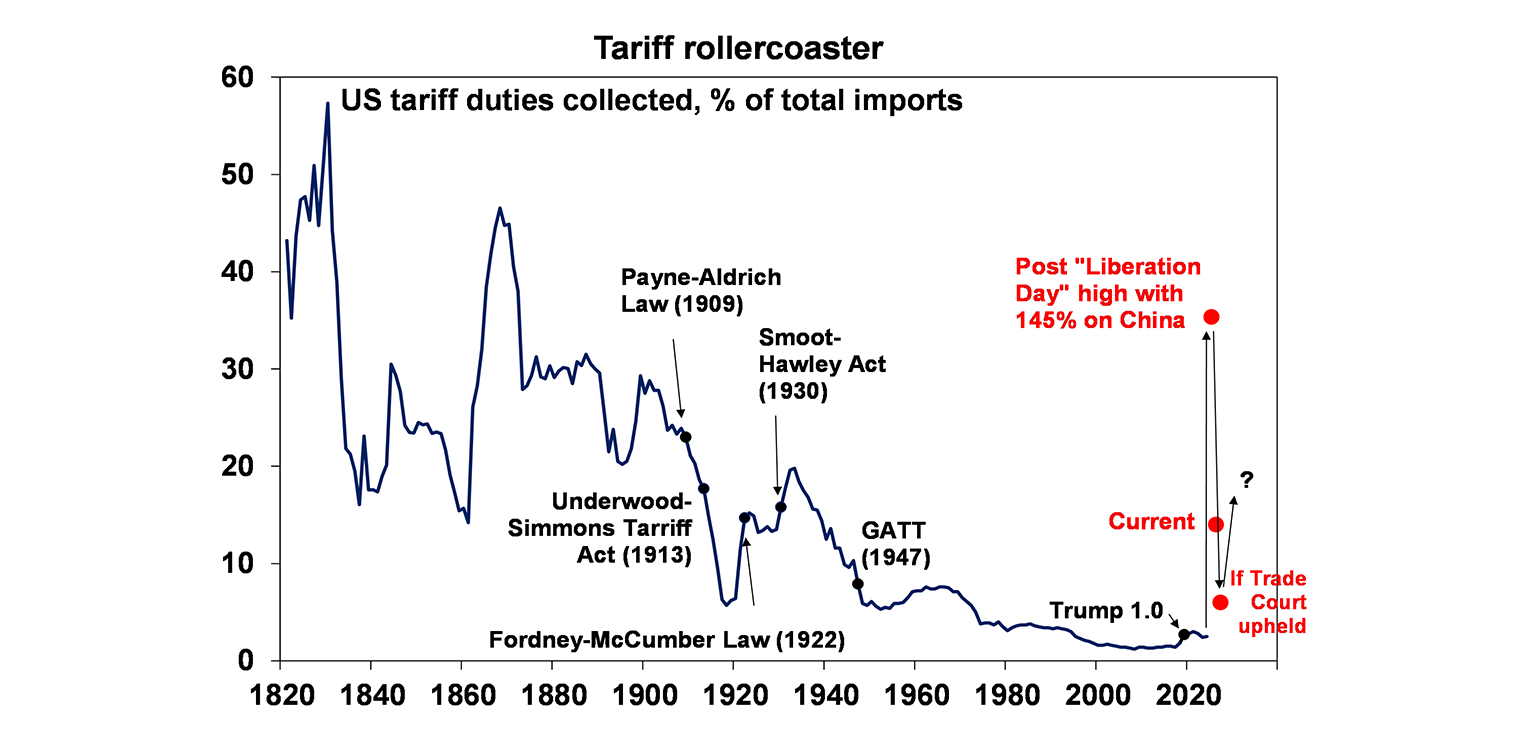

This is driving a rollercoaster ride with the average announced US tariff rising from 2.7% at the start of the year, to peak over 30% post Liberation Day, to be now around 14% and potentially falling back to 6 or 7% if the Trade Court decision is upheld. But, it’s likely to rebound as more sectoral tariffs are put in place, Trump wins the appeal or moves to other ways to authorise the tariffs and once trade talks end resulting in higher tariffs if the talks don’t go well, as appears to be the case with China and Europe.

Trying to make sense of all this in terms of the end point for the tariffs and the ultimate economic impact is not easy, creating significant uncertainty. And all the flip flopping has given rise to the TACO acronym that “Trump always chickens out”. Naturally Trump took offence at this, labelling a journalist’s question about it “nasty” and said what he is doing is negotiation: “set a ridiculous high number” and then “go down a little bit” but it still looks like he backs off after getting scared about the fallout and the more he does it the less credible his threats become. Which partly explains why share markets are responding a bit less to tariff news. The trouble is that the resilience in markets and Trump’s annoyance with the “chicken” label and court challenges risk Trump ramping up in pressure again – which is what we saw with the 50% tariff on steel and aluminium. So, this still has a long way to go before it’s resolved particularly with the 90-day deadlines approaching (9 July, except China which is 12 August). In the meantime, a new worry is emerging around worsening US public debt, with concerns about a crisis and upwards pressure on bond yields.

Why the flare up in worries about US public debt?

Fears about too much debt have been around ever since debt was invented. Apart from in emerging countries, notably Argentina, prior to the GFC these concerns were mainly around private debt but since then the focus has shifted to public debt as it’s risen relatively. This was evident in the Eurozone debt crisis last decade.

For the US, concern has long been expressed about the size of its budget deficit and rising trend in public debt - in fact, the “debt clock” near Times Square first appeared way back in 1989 and there was a brief flurry of concern after Standard and Poor’s downgrade of America’s credit rating from AAA to AA+ in August 2011. But debt worries at the time came to nothing as the falling trend in bond yields meant that despite rising public debt, it wasn’t really a problem in terms of servicing it.

However, this may be starting to change as the following have served to refocus attention on the rising level of US public debt:

higher bond yields since the pandemic have pushed US Federal interest payments to a record 18% of tax revenue;

the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) tax cut bill – which extends Trump’s 2017 tax cuts and adds in a few more – implies an extra $US3 trillion or so added on to the budget deficit over ten years;

Moody’s downgrade of the US credit rating from AAA to Aa1; and

a growing debate about the merits of investing in the US given: Trump’s chaotic policy making around tariffs & DOGE; attacks on Fed independence, regulatory agencies, the rule of law and universities; and a tax on foreign investors in the US (Section 899 of the OBBBA) – all call into question “US exceptionalism” and its “safe haven” status.

While Moody’s was just catching up to downgrades by S&P and Fitch, US Federal debt is now much higher than it was when S&P downgraded the US in 2011. See the next chart. And projections by the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) indicate the tax cut bill will keep the budget deficit around 7% of GDP which is well above the 3% or so of GDP necessary to stabilise the debt to GDP ratio. Tariff revenue and some savings on spending are providing only a partial offset to the tax cuts. Which means the debt to GDP ratio will keep rising – taking gross Federal debt from around 124% of GDP to around 155% of GDP by 2035.

Along with current bond yields, this will mean that net interest costs as a share of revenue and GDP will rise further into record territory.

The last time US Federal debt interest payments were around 3% of GDP and taking up around 18% of tax revenue was in the early 1990s. This ushered in a period of fiscal austerity and together with falling inflation and interest rates eased the pressure substantially coming in the 2000s.

This time around, US policy makers are not focussed on bringing the budget down. Instead, they are adding to it with the OBBBA tax cut bill. And the falling US dollar suggests foreign investors may be becoming less keen on buying US Treasuries and hence financing ever rising US public debt, which in turn runs the risk of even higher US bond yields. Ever higher US bond yields – the so-called “bond vigilantes” - could put pressure on Trump and Congress to put the deficit and debt on a more sustainable path. This would require Congress to agree on some sort of fiscal austerity but the process to get to this could be volatile. And getting the budget deficit under control can be quite difficult if the objective is to cut taxes – sure, tariffs are a tax hike but the revenue they will raise will be far less than the cost of the latest tax cuts. The problem on the spending side is that of the $US7bn in annual Federal spending about 63% is mandatory (on social security, Medicare, etc), 18% is net interest, about 12% is defence (also untouchable!) leaving only about 7% which is up for grabs i.e. about $US500bn – which partly explains why Elon Musk even with a chainsaw did not get far. His DOGE claims to have saved $US160bn against an initial goal of $US2 trillion but it’s likely much less than that.

Maybe it’s not quite that bad

This all sounds kind of hopeless! But there are several reasons not to get too gloomy.

First, the US, like Europe and Japan, borrows in its own currency so a public debt/foreign exchange crisis requiring IMF support - like has occurred in Argentina and other emerging countries which borrow predominantly in US dollars - is not going to happen.

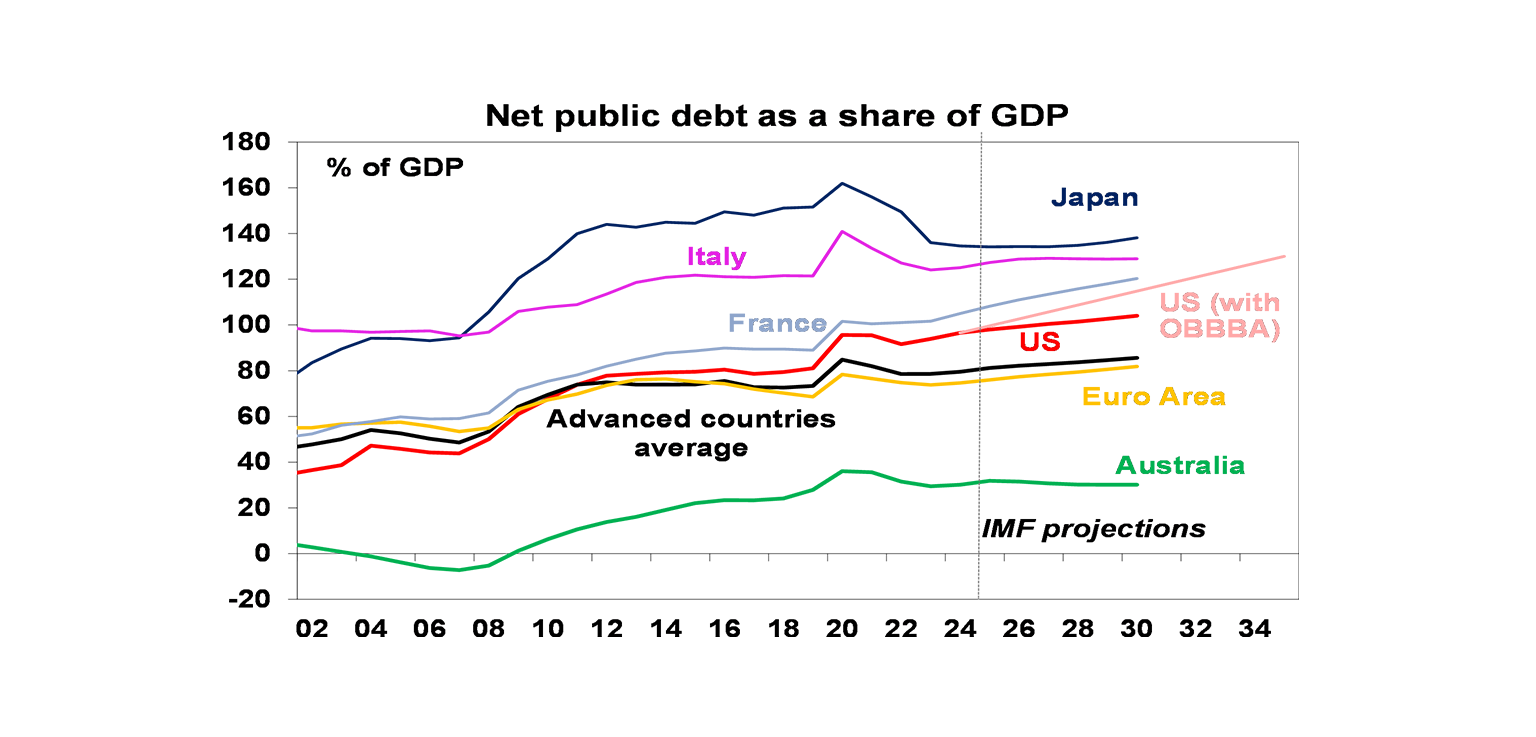

Second, while US public debt relative to its GDP is above the average for advanced countries and well above Australia, it’s less than in Japan (which has seen its own concerns with rising JGB yields partly due to contagion from US worries), Italy and France. And they are managing to get by.

Thirdly, Trump’s supply side policies – tax cuts and deregulation – could drive stronger economic growth which could ease the debt burden. (A counter is that some of Trump’s policies – tariff walls, less immigration, cuts to research & university funding – could reduce potential US growth.)

Finally, if push came to shove the US Federal Government has plenty of scope to raise taxes to service its debts in the event of a major problem and likewise in the extreme the Fed could be called on to buy bonds.

…but it still poses upside risks to bond yields

While the US is unlikely to see a full blown public debt crisis, there’s a high risk that the combination of a deteriorating outlook for US public debt along with Trump’s erratic policies and threats to things that have driven strong US growth, will see global investors demand a higher risk premium to invest in US shares, bonds and the $US. I suspect this is likely to be a slow burn and for now US tech and AI dominance will serve as a powerful offset. But it means ongoing bouts of high uncertainty and volatility, particularly given that right now the US share market is offering around a zero risk premium over bonds – as measured by the gap between the forward earnings yield and the 10-year bond yield.

Implications for Australia

There are several implications for Australia.

First, the good news is that our level of public debt is low. However, our good luck on the back of high commodity prices could end at some point.

Second, some worry that rising US bond yields could mean higher Australian bond yields and hence fixed mortgage rates, but this seems unlikely if it reflects investors’ desire for a higher risk premium on US assets and Australia comes to be seen as relatively safer.

Third, another round of weakness in the US share market on the back of tariff and public debt worries would flow through to Australian shares - albeit we may fall by less as we saw in April.

Finally, it’s possible that the $US is losing its ‘safe haven’ status that could see it fall rather than go up in a crisis. This mean the $A may behave a bit less as a shock absorber in a crisis by not falling as much as would normally be the case. Time will tell, but if this is the case then more of the burden could fall on the RBA to help protect the economy in rough times.

Concluding comment

Shares are now back near record highs and look like they will break through to new highs on the back of underweight investors buying back in, the TACO (“Trump always chickens out”) trade and shares looking strong from a technical perspective. But the risk of tariff and US public debt worries driving a new bout of weakness through the seasonally weak period out to September is high. The sooner Trump pivots to more consistently market-friendly policies the better, but that may be a way off.

For most investors though, including super members, trying to time all this is likely to be hard so the best approach is to stick to a long-term investment strategy to take advantage of shares rising trend over time.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP

You may also like

-

The outlook for Australian shares – is the long underperformance over? Australian shares have had a strong start to 2026 with the ASX 200 up 3.3% and flirting with a new record high. The local market has also outperformed US shares which are down 0.1% and global shares which are up 1.6%. However, this could just be noise and follows a significant underperformance against US and global shares since 2009. -

Weekly market update - 20-02-2026 Global share markets mostly rose over the last week. Worries about AI and tech valuations took a breather and the US Supreme Court decision to strike down Trump’s emergency power tariffs with Trump immediately announcing a replacement were seen as having little impact on the US growth outlook but were seen as positive for other countries. -

Econosights - An update on global debt and fiscal policy With the International Monetary Fund releasing their Global Fiscal Monitor recently, AMP's Senior Economist, Diana Mousina provides an update on the global debt situation and recent fiscal policy announcements.

Important information

Any advice and information is provided by AWM Services Pty Ltd ABN 15 139 353 496, AFSL No. 366121 (AWM Services) and is general in nature. It hasn’t taken your financial or personal circumstances into account. Taxation issues are complex. You should seek professional advice before deciding to act on any information in this article.

It’s important to consider your particular circumstances and read the relevant Product Disclosure Statement, Target Market Determination or Terms and Conditions, available from AMP at amp.com.au, or by calling 131 267, before deciding what’s right for you. The super coaching session is a super health check and is provided by AWM Services and is general advice only. It does not consider your personal circumstances.

You can read our Financial Services Guide online for information about our services, including the fees and other benefits that AMP companies and their representatives may receive in relation to products and services provided to you. You can also ask us for a hardcopy. All information on this website is subject to change without notice. AWM Services is part of the AMP group.