Key points

The last decade has seen productivity stagnate in Australia. This has curtailed growth in living standards and real wages.

Policies to boost productivity include: deregulation; more housing supply; a cap on public spending; and tax reform.

Unfortunately, the political pendulum has moved against many of the necessary policies and the lack of a “crisis” like Labor faced in the 1980s may make many reforms difficult.

But the good news is that the Government now recognises the problem and is starting to focus on how to boost it.

“Productivity isn’t everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything”. Paul Krugman, Economist

“If you walk into any pet shop in Australia, what the resident galah will be talking about is microeconomic policy.” Paul Keating, Australian Treasurer, 1989 when exasperated about calls for more productivity reforms.

Introduction

Former RBA Governor, Philip Lowe noted that boosting Australia’s weak productivity “should be the issue that dominates economic discussion”. At last, this seems to be happening. In the run up to the Federal election there was much discussion about Australia’s falling living standards and poor productivity. And the Government has recognised the issue with the Treasurer to host an “Economic Reform Roundtable” next month. This is good news. But why is productivity a hot topic at present in Australia?

What is productivity?

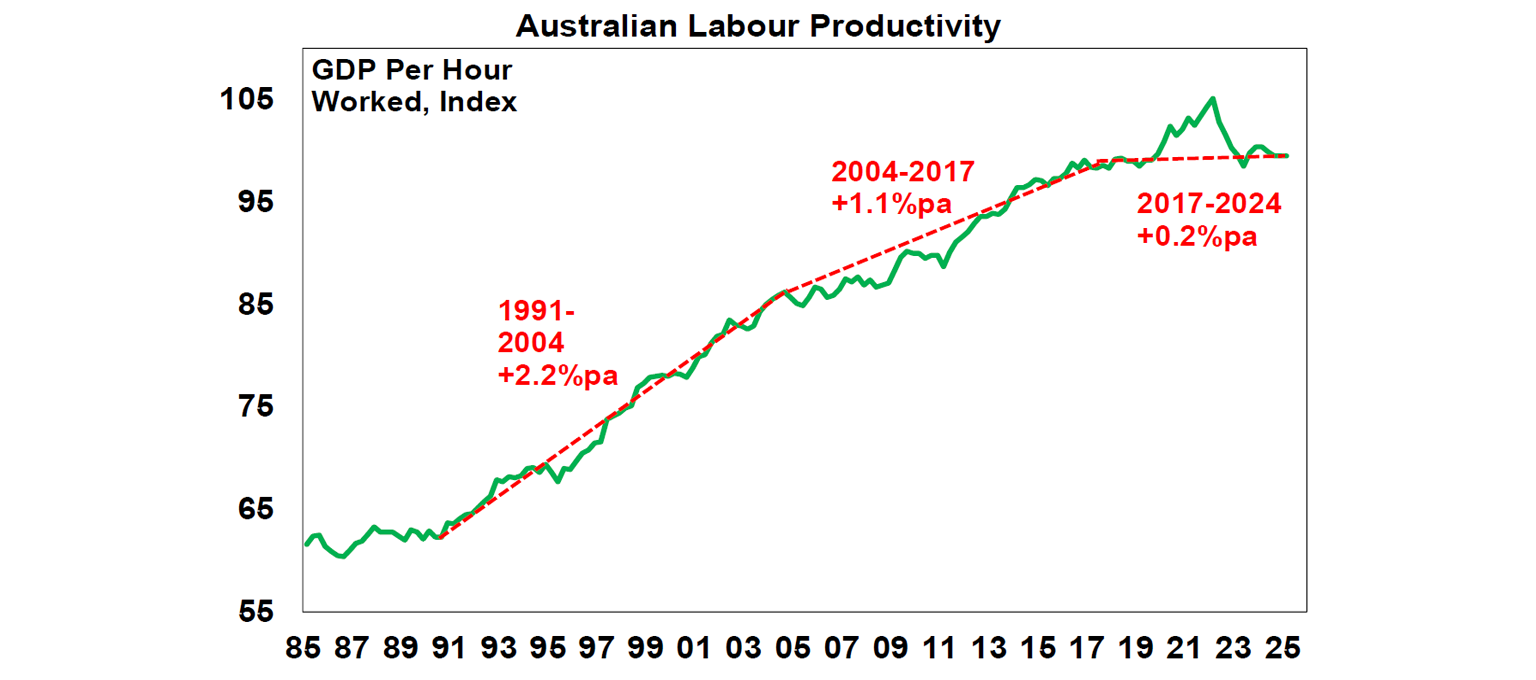

Productivity refers to the level of economic output for a given level of labour and capital inputs. Increased productivity means more is being produced for given inputs. Output usually refers to Gross Domestic Product and it’s common to refer to measures of labour productivity, i.e. GDP per hour worked. So, it is really about producing more for the same amount of work (or less). The next chart shows the level of GDP per hour worked over the last forty years. We saw rapid productivity growth from the early 1990s to the mid-2000s but over the last decade it’s stagnated.

Why does productivity matter?

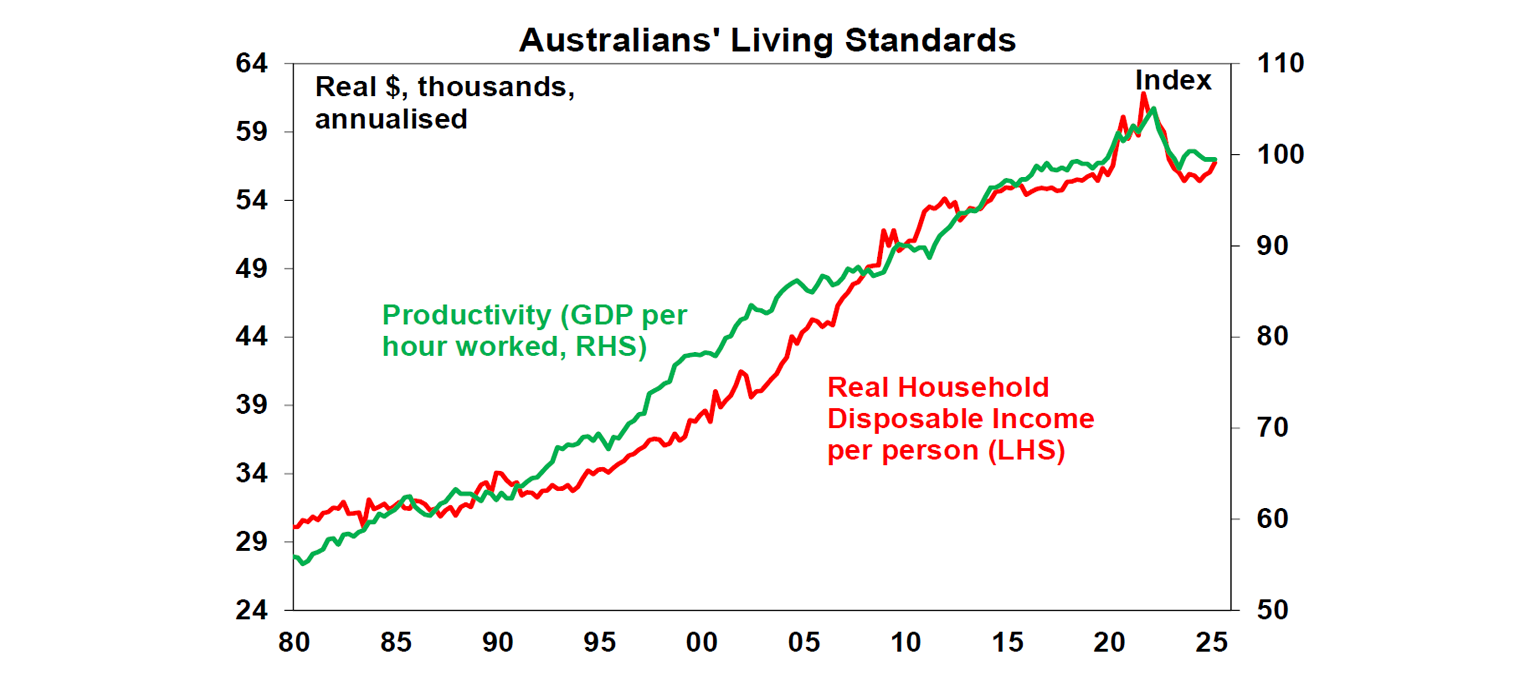

Rising productivity is the main driver of rising material living standards. The more we can produce from our work the more we can earn and the more we can consume. One measure of living standards is real household disposable income per person and as can be seen in the next chart, there is a rough correlation between it and productivity with the latter helping drive a rapid rise in income levels into the 2000s but with little growth over the last decade. So poor productivity is central to the “cost of living crisis”. This is also evident in the “per capita recession” since 2022.

We have partly made up for poor productivity growth by faster population growth, but this does not address living standards per person. Likewise, the slump in productivity has been masked by strong national commodity earnings but we cannot rely on this indefinitely.

Why is it relevant for decent wages growth?

If wages growth is 4% and output per worker goes up by 1.5% then the increase in labour costs for business is 2.5% which if passed on as higher prices is in line with the RBA’s 2-3% inflation objective. But if wages go up 4% and productivity growth is zero, business costs go up 4% and they can either pass this on to their customers likely resulting in inflation above target or take a hit to their profit margins or both.

So decent productivity growth is the secret sauce that enables decent growth in real wages while at the same time keeping inflation low. This in turn ensures decent tax revenue growth enabling the government to provide the services people expect and provides the basis for solid sustained real growth in profits and hence returns for investors. The Australian Productivity Commission points out that if productivity growth can be returned to its historic average around 1.5% pa then an average full-time worker would be at least $14,000 better off by 2035.

But why has productivity growth slumped?

The surge in productivity that got underway in the 1990s reflected a wave of reforms that started in the 1980s and boosted the supply side of the economy. This included financial deregulation, labour and product market deregulation, reduced trade barriers, competition reforms, privatisation, tax reform and an improvement in educational attainment. A range of factors have contributed to slower productivity growth since:

The benefits from past economic reforms have largely been seen and there has been little in the way of new reforms since the GST and some backsliding – e.g. the labour market has become less flexible.

A surging population over the last 20 years with inadequate infrastructure and housing supply has led to urban congestion and poor housing affordability which contribute to poor productivity growth – notably via increased transport costs and speculative activity around housing diverting resources from more productive uses.

The retirement of the baby boomer wave and replacement with a wave of less experienced millennials and Gen Z may have slowed productivity growth (just as baby boomers did in the 1970s).

Since the 2000s non-mining business investment has slowed.

Market concentration has risen in key industries, cutting competition.

We rejected an efficient mechanism (carbon pricing and trading) to determine the best way to cut carbon emissions in favour of a “hotchpotch of measures” which contributed to high energy costs.

The services sector, notably the care economy, has grown as a share of the economy and it is more labour intensive and less productive.

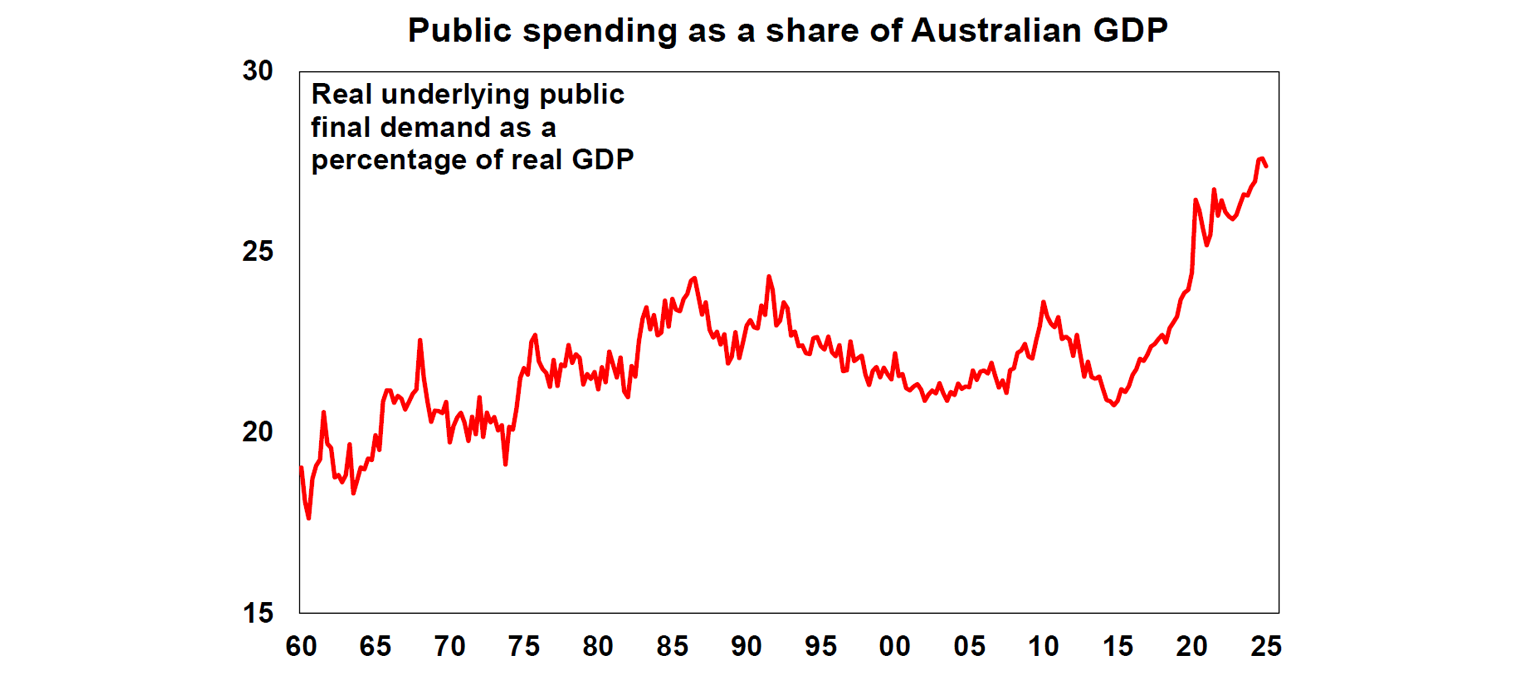

Related to this has been strong growth in the last few years in public spending to a record high as a share of GDP and it is attracting labour and other resources from the more productive private sector.

And the pandemic distorted productivity by first boosting it as (low productivity) services activity was curtailed by lockdowns and then reducing it as services activity rebounded with reopening.

The last point was temporary, but the other factors in the list above are longer lasting. More generally high commodity prices and the absence of a “crisis” have meant that there has been little pressure on policy makers to undertake more productivity enhancing reforms.

But maybe it’s not as bad as it looks?

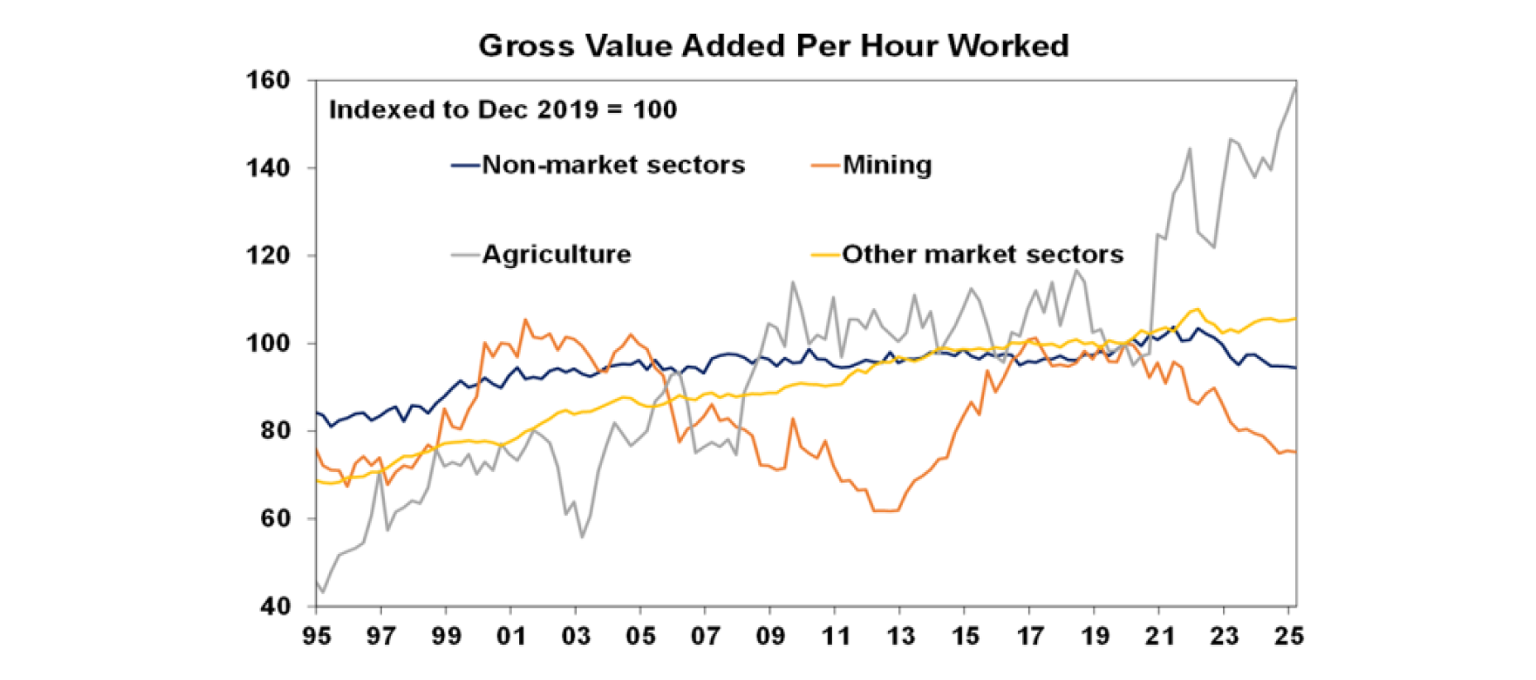

There are several arguments that it’s not as bad as it looks. Firstly, Productivity Commission research suggests that healthcare sector productivity has actually been far more robust than reported once quality improvements like enabling longer lives are allowed for and it’s possible that productivity is similarly being underestimated in other services/non-market sectors in the economy. And in the market sector (which is dominated by the private sector) of the economy weak productivity has been largely due to the mining sector (see the orange line in the next chart) which tends to be very cyclical, more than offsetting strength in agricultural productivity (grey line), but other market sector productivity (yellow line) has been growing in line with its longer term trend.

So maybe it’s not quite as bad as it looks. The trouble is that the “cost of living” crisis and slump in real household disposable income are both real and suggest that the slump in productivity is also real.

So how do we boost productivity?

The key is to acknowledge the problem, discuss the options and chart a path forward. And the good news is that the Economic Reform Roundtable is ticking off the first two of these. Fortunately, there are plenty of good ideas. Key areas for action include the following:

Tax reform to rebalance from income tax to a broader GST, compensate those adversely affected, and remove nuisance taxes like stamp duty to incentivize work effort and investment, better allocate resources and reduce the burden on younger generations as the population ages. This sounds politically difficult but if combined with some measures to cap property tax concessions (like cutting the overly generous capital gains tax discount) and better tax gas exports a broad consensus could conceivably be reached. While some advocate a wealth tax to deal with rising wealth inequality, a better option may be inheritance tax as it’s a less distortionary tax.

Limit government spending to below 25% of GDP. If we want more government services, we need to find others to cut.

Deregulate product and labour markets to remove red tape, boost flexibility and make it easier to get things done. Unfortunately, the Government has ruled out industrial relations changes but there is much that can be done here, e.g. to speed up home building.

Provide more incentives, in particular by tax deductions, for companies to invest and adopt new technology including AI (although AI runs a risk of higher short-term white-collar unemployment).

Boost workforce capability by improving education and training.

Competition reform to reduce market concentration.

Match population growth to the ability to supply new homes.

Boost service delivery productivity in the care economy, including by focusing more on prevention in healthcare.

Maintain high levels of infrastructure spending to reduce congestion, lower transport costs & allow more to live away from expensive cities.

So, what are the prospects for serious reform?

The main constraint to boosting productivity is arguably political. Support for the economic rationalist policies of the 1980s has long faded. And past periods of reform have notably been triggered by a serious economic crisis forcing policy makers to act and we don’t have a crisis (yet). So, a period of intense economic reform like pet galahs were talking about two generations ago seems unlikely. At least until there is a real crisis! In particular, action to rebalance to the GST and de-regulate the labour market already looks to be off the table. That said some action around removing excess regulation and some tax reform looks likely. I hope!

Implications for investors

Stronger productivity would be good news for investors as it would boost profit growth and allow lower than otherwise inflation and interest rates.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP

You may also like

-

Econosights - An update on global debt and fiscal policy With the International Monetary Fund releasing their Global Fiscal Monitor recently, AMP's Senior Economist, Diana Mousina provides an update on the global debt situation and recent fiscal policy announcements. -

Oliver's Insights - Nine key charts for investors Share markets have had a bit of a wobbly start to the year, particularly in the US. This note looks at nine key charts worth watching. -

Weekly market update - 13-02-2026 US shares fell over the last week on the back of ongoing concerns about AI disruption, excessive related capital spending and tech sector valuations.

Important note

While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, neither National Mutual Funds Management Ltd (ABN 32 006 787 720, AFSL 234652) (NMFM), AMP Limited ABN 49 079 354 519 nor any other member of the AMP Group (AMP) makes any representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided. This document is not intended for distribution or use in any jurisdiction where it would be contrary to applicable laws, regulations or directives and does not constitute a recommendation, offer, solicitation or invitation to invest.