Key points

The provision of appropriate childcare services is important because it helps to lift labour force participation.

In Australia, the government’s childcare subsidy has not helped to reduce childcare inflation over time. The subsidy has allowed more for-profit businesses to enter the childcare industry. But, this model does not appear to have rewarded families given numerous regulatory failures. Listed childcare providers performance has also struggled.

Short-term government involvement is needed from a regulation point of view. Longer-term, moving to a universal-based childcare model makes sense along with the provision of more part-government pre-schools, in coordination with the state, local and federal governments.

Introduction

In recent years, the Labor government expanded the childcare subsidy to cover more families, removed the activity test on parent work hours, expanded parental leave access and awarded above-average wage increases to childcare workers. A recent ABC Four Corners investigation into some of the regulatory failures in the childcare system got me thinking about issues in the sector, which I have covered in this Econosights.

Some background on Australia’s childcare system

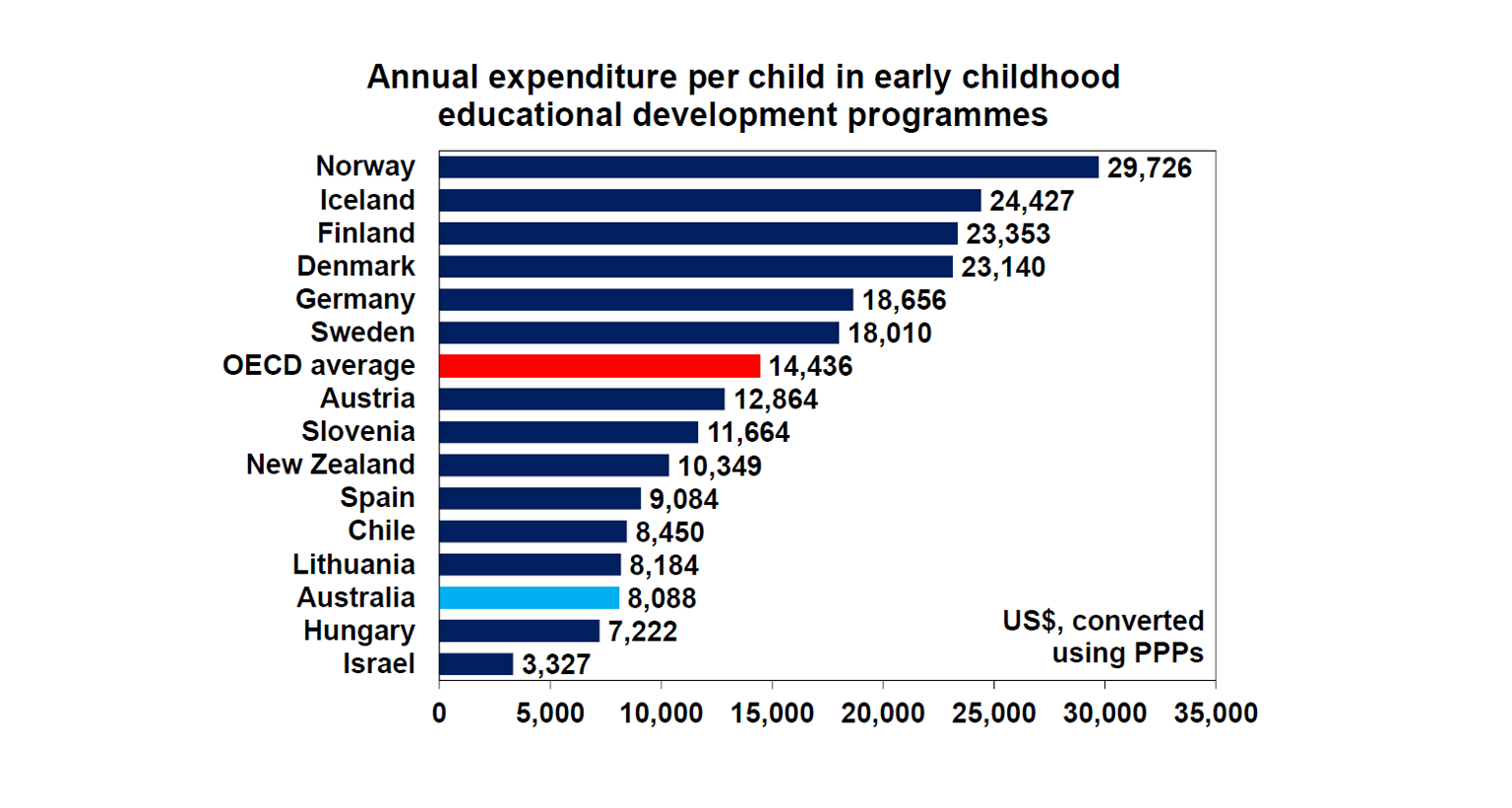

In mid-2024, around 1.4 million children (aged 0-12) accessed some form of early childhood care, consisting of pre-primary childcare services which can be long-day care (usually by for-profit providers), family day-care, in-home care (nannies) and pre-schools (for children aged 4-5 (which often have funding from state/federal governments), and after school care (for those aged 5-12). In Australia, there is no legal requirement to attend early childhood care and as a result, Australia appears to spend a lower amount per child in early childhood programmes relative to OECD peers.

However, most children do get early childhood care at some stage. For example, data from the Productivity Commission indicated that around 50% of 1-year olds and 90% of 4-year olds attend some form of early childcare while around 15% of school children go to after school care.

Impacts on the economy

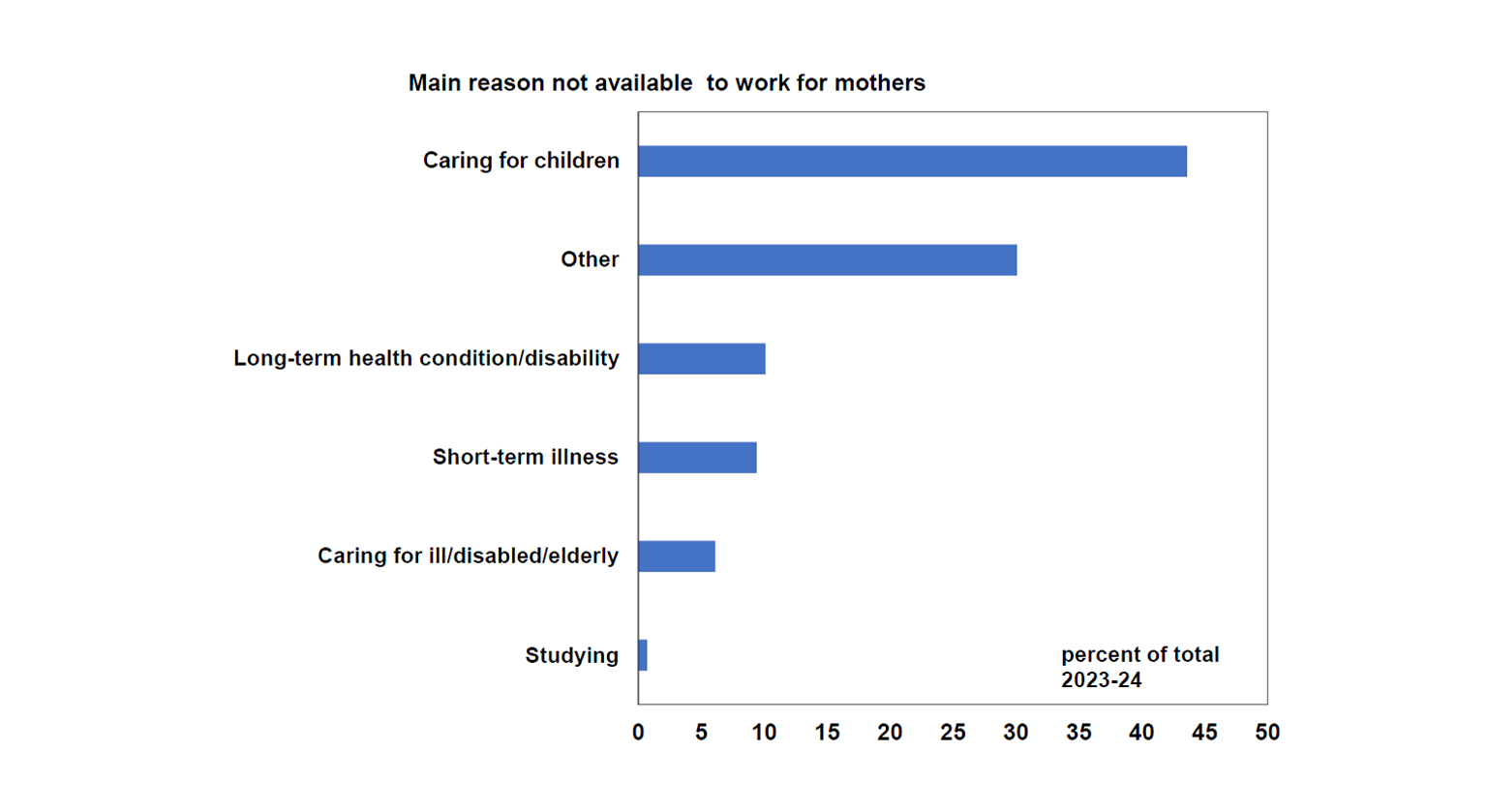

The most obvious impact of the provision of childcare services is on the female participation rate. Caring for children is listed as the top reason for a female not being available to start a job (see the chart below).

That is not to say that many women don’t choose this option themselves. When asked what the main reason is behind childcare being a barrier to female participation,39% said care was not available, 24% said the kids were not at the right age for care and 24% of women said that they preferred to look after their children. Interestingly, the cost of care was not one of the top reasons (although this used to be more of an issue and has decreased more recently after recent changes to the subsidy).

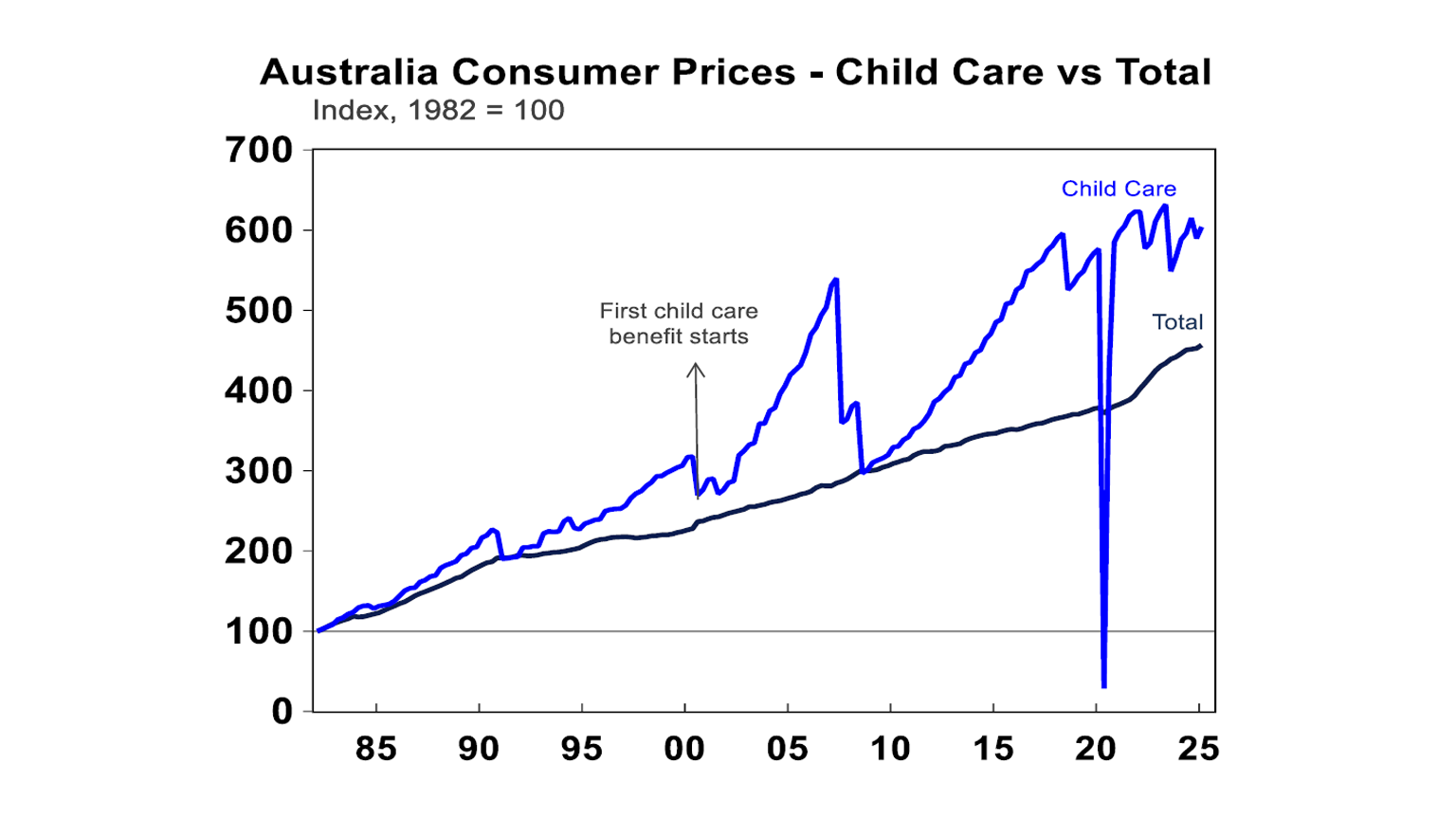

However, high child care costs in Australia are a problem, despite the childcare subsidy. Childcare inflation has run well above headline consumer prices since the mid-1980’s, but particularly since 2010 (see the next chart).

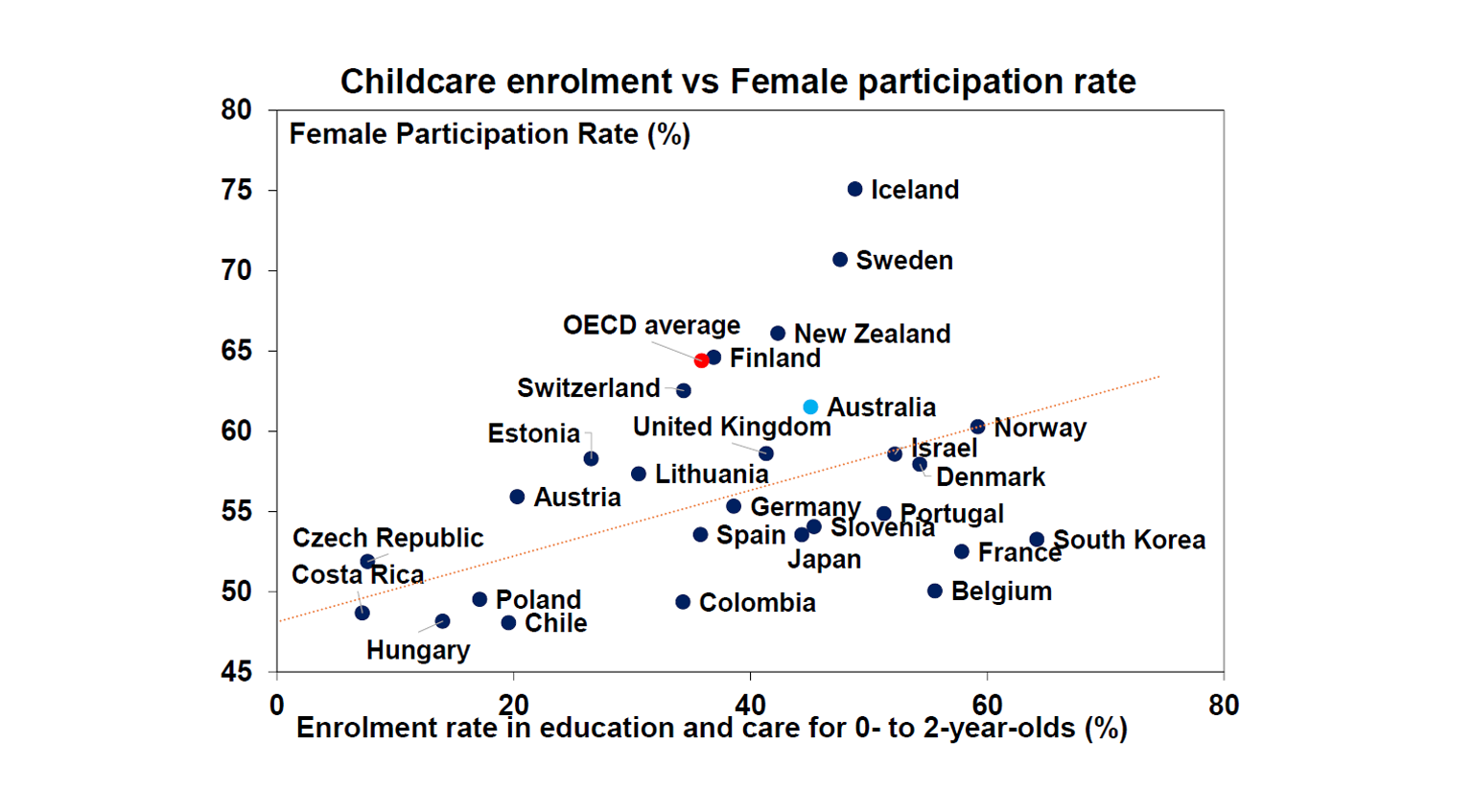

We know that when childcare enrolment rates increase, female participation goes up (see the chart below). But, it is not just about making the fees cheaper that will help workforce participation. Analysis from the Productivity Commission has shown that ensuring that care is available, having access to appropriate services and ensuring they are cost effective all help to lift female participation in the labour force. The female participation rate in Australia reached a record high of 63.4% (thanks to high employment growth in female-dominated sectors), well up from just over 40% in the 1980s. But, the part-time employment rate of mothers in Australia is high at 43.2% relative to the OECD average at 22.6%. The Productivity Commission estimates that if all barriers to childcare were removed, this would lead to an extra 1% increase in employment. While this isn’t particularly significant, especially as female participation is already at a record high, the benefits to expanding childcare extend beyond participation to giving women flexibility and setting children up for better education outcomes. The experience of the pandemic has also shown that job flexibility is important, as working from home can help boost participation for both men and women.

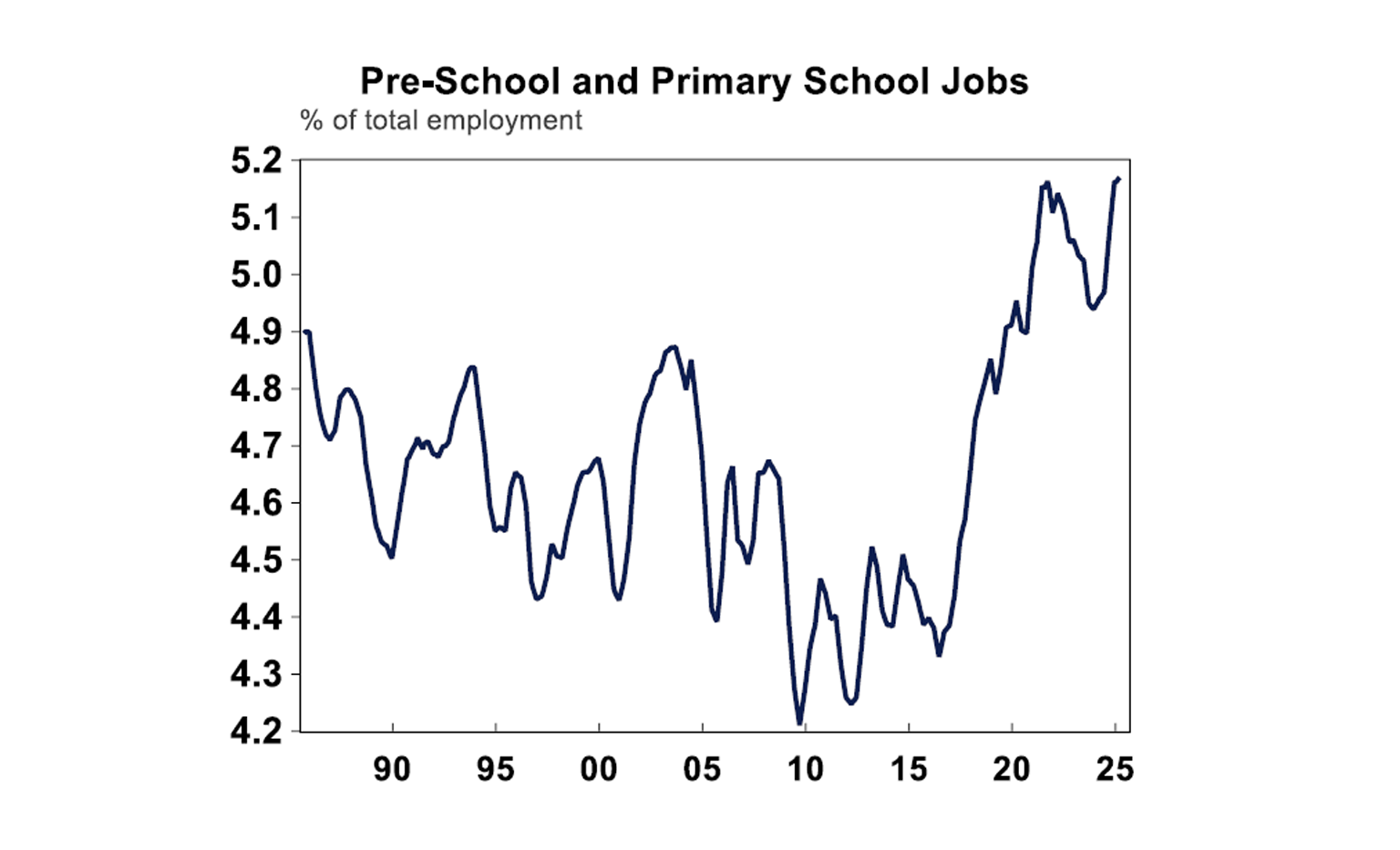

Pre-school and primary jobs make up around 5% of Australian jobs (see the chart below) and have had a boost in the post-pandemic period, with education being one of the fastest growing employment sectors of recent years. Women make up over 70% of education jobs in Australia, so the boost in pre-school and primary jobs has been one reason behind the rise in female participation. Education job vacancies also remain elevated, relative to other industries which shows that there are still some shortages of skills in the sector.

Implications for government

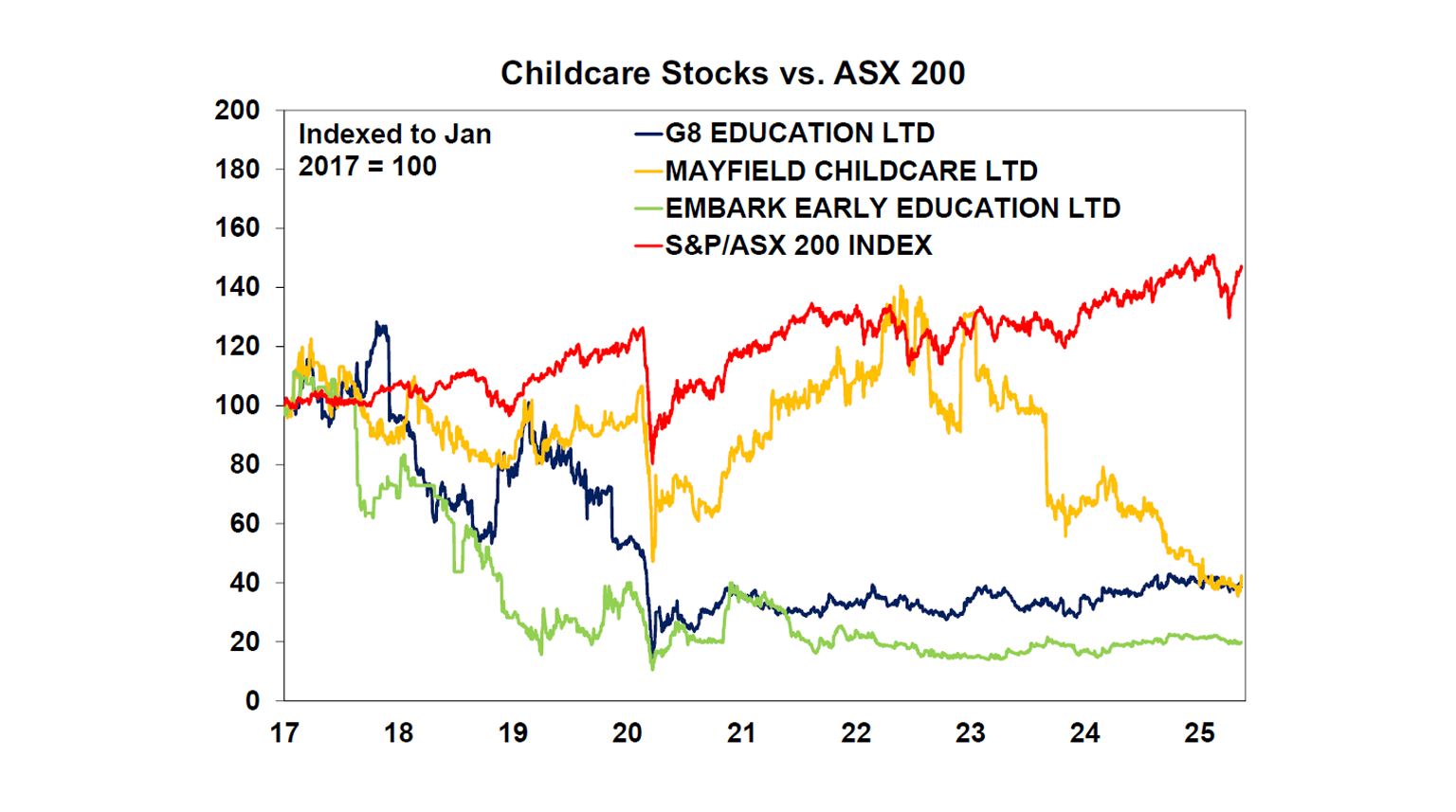

The provision of the childcare subsidy and more demand for childcare spots has meant that more for-profit providers have moved into the space. It’s estimated that around 70% of long-day cares are operated by private providers. However, when looking at these providers compared to overall performance on the ASX, the outcomes weren’t particularly favourable, with the 3 listed providers underperforming the ASX200 over many years by a considerable amount (see the chart below).

Fundamentally, the purpose of the early childcare sector (which is about the provision of education and care) stands at odds with profit generation, much like other parts of the economy like health, aged care and education.

In the short-term, the priority of the government needs to be on regulation in the industry, as expressed by the ABC Four Corners investigation. In particular, the centres that are not meeting national quality standards but rather “Working Towards” should have serious consequences, rather than being allowed to continue operating.

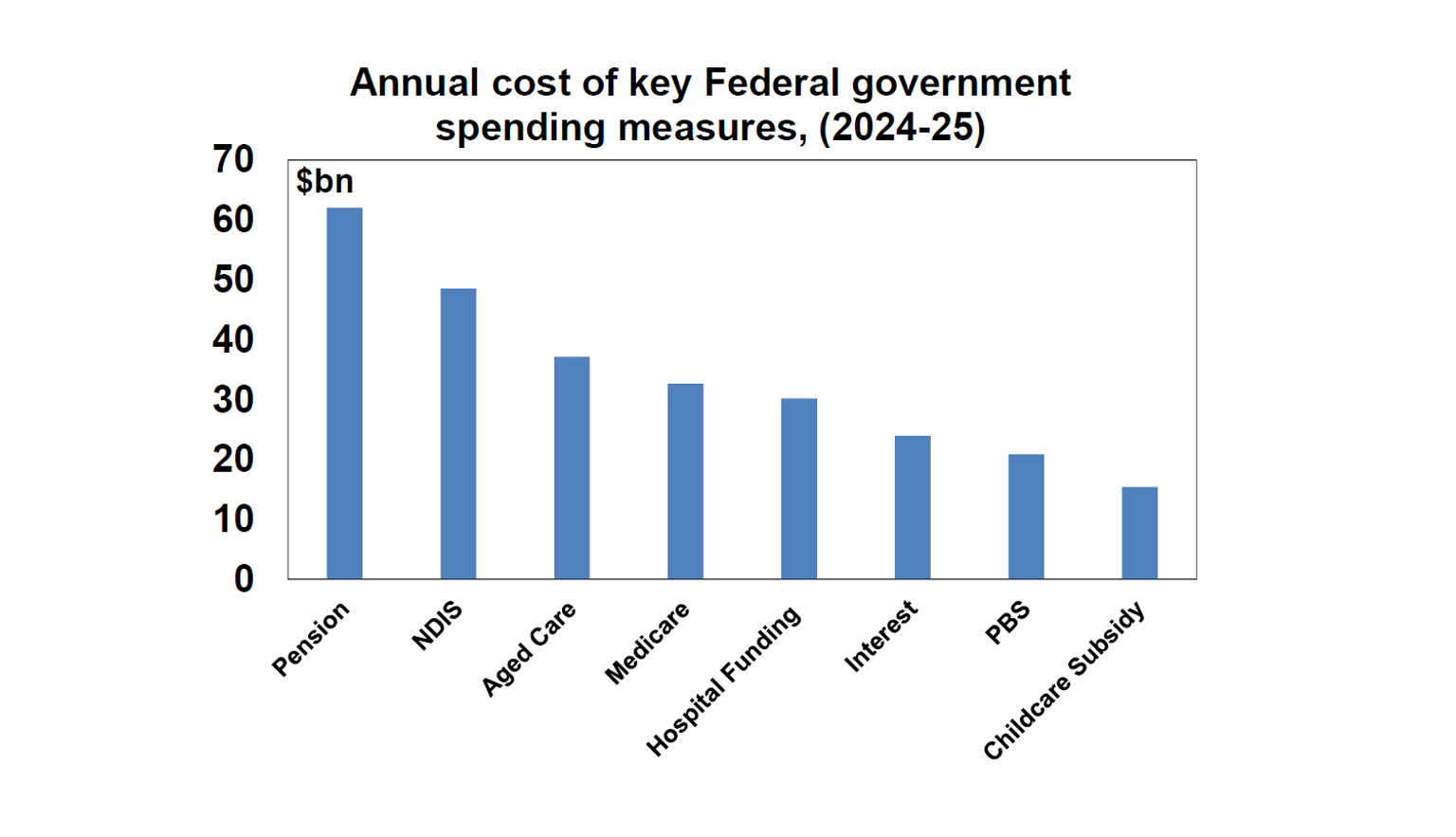

The longer-term priority for government is moving more to a universal-based childcare model. This is a system where every child, regardless of where they live or family income has access to high-quality early childhood education in the years before they start school. In 2024-25, the childcare subsidy is expected to cost the government $15bn (see the chart below), at the lower range of some of the other key spending priorities. Instead of increasing the childcare subsidy (which just looks to increase childcare inflation and push more for-profit providers into the industry), state, local and federal governments should coordinate to open more part-government funded pre-school centres. State education budgets could be used for this.

The use of childcare has grown over time and this will continue as families are likely to move away from capital cities and their hometowns for housing affordability reasons (and therefore can’t rely on family support for care). Recent findings have shown that the childcare sector in Australia is struggling to handle growing demand and private involvement in the sector has not rewarded the providers or the families using the services. There needs to be more government involvement in the early childcare sector in the shot-term via regulatory measures and in the longer-term to move to a universal-based childcare model which may increase the government’s role in the sector in the short-term before allowing the private sector to have more control in the longer-run.

Diana Mousina

Deputy Chief Economist, AMP

You may also like

-

Four ways to maximise your Self-Managed Super Fund (SMSF) Here are four practical tips that could help you unlock more value from your SMSF, from managing cashflow to exploring property investment. -

How to buy an investment property through a Self-Managed Super Fund (SMSF) Discover how buying an investment property through a SMSF could help boost your retirement savings. -

Oliver's insights - Inflation, rate hikes and public spending – Q&A Much in economics is shades of grey and so subject to some debate. This has certainly been the case around the rebound in inflation in Australia, the RBA’s response and what’s driving it. This note looks at the key issues.

Important note

While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, neither National Mutual Funds Management Ltd (ABN 32 006 787 720, AFSL 234652) (NMFM), AMP Limited ABN 49 079 354 519 nor any other member of the AMP Group (AMP) makes any representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs.

This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided. This document is not intended for distribution or use in any jurisdiction where it would be contrary to applicable laws, regulations or directives and does not constitute a recommendation, offer, solicitation or invitation to invest.