Introduction

The 8th of March marks International Women’s Day. The macroeconomic backdrop has improved for women in Australia over the past year, mostly as a result of better labour market conditions and the Labor government’s policies to reduce the cost of childcare. We look at these issues in this edition of Econosights.

Women in the Australian labour market

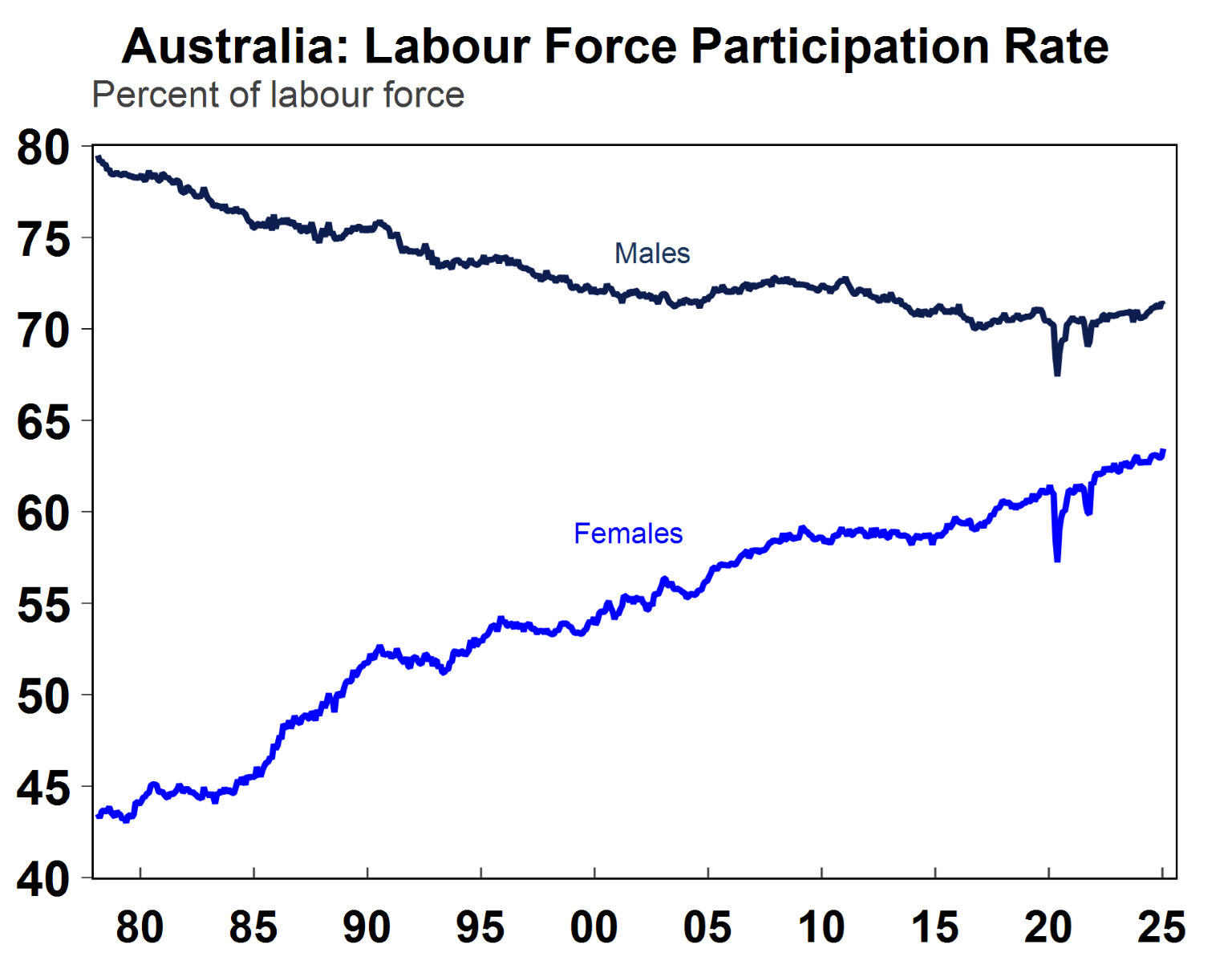

The female participation rate (the number of women either employed or unemployed as a share of the labour market) has risen over the past year to a new record high of 63.5%, from 62.6% a year ago. The male participation rate has also risen to 71.3%, from 70.5% a year ago. Female participation is well above the ~43% that was recorded in 1978. The pandemic has led to a big step-up in female particiaption, relative to males. This has occurred from higher work flexibility post-pandemic and the increase in jobs in the care economy, which have a higher female share.

In Australia, nearly 43% of women in the labour market work part-time, more than double the 20% of men who work part-time.

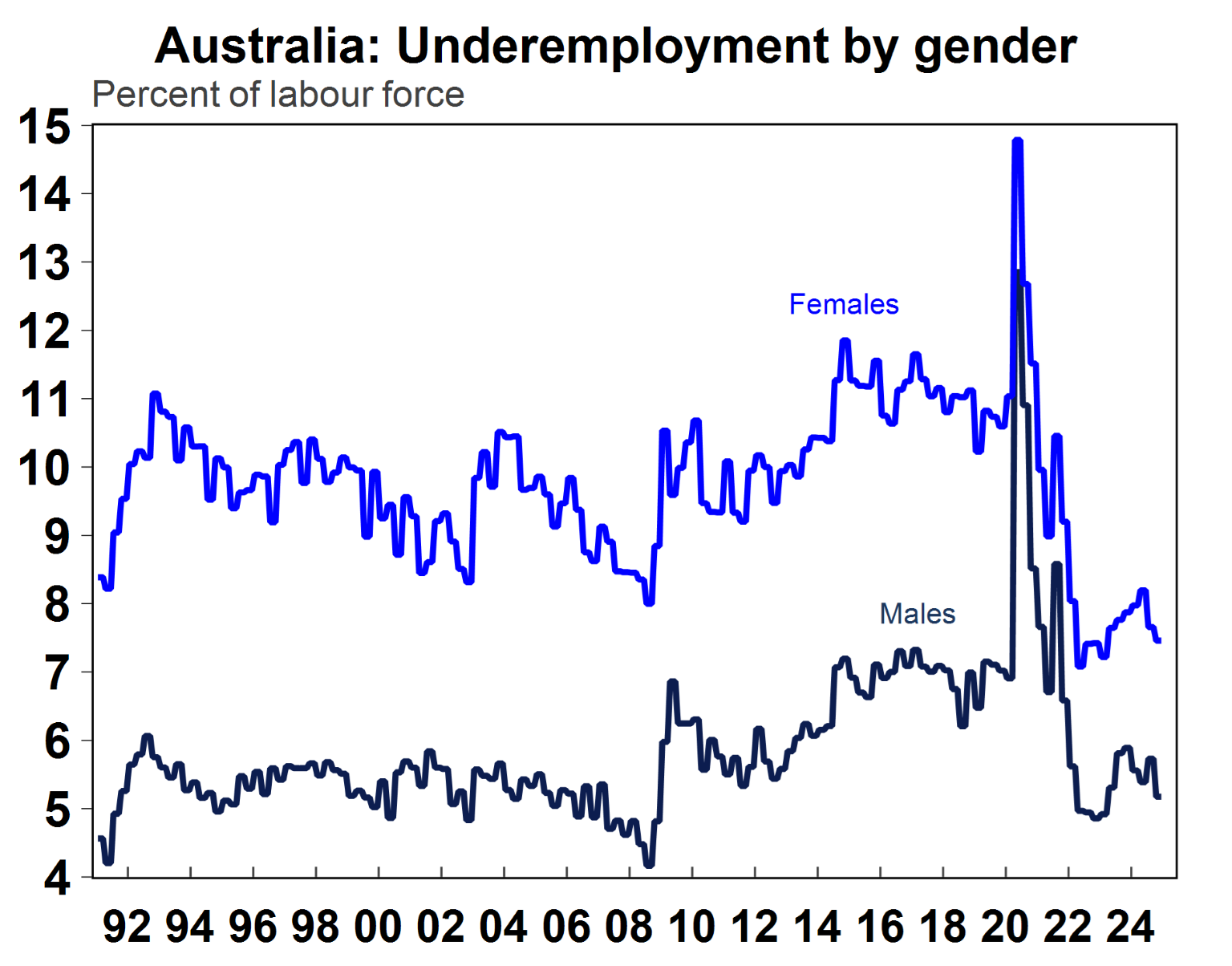

The higher rate of part-time participation by females partly explains higher “underemployment” (i.e. some females wanting to work more hours). Female underemployment is 7.5% and males is 5.2% (see the chart above). Although, female underemployment has fallen to its lowest period on record (outside of the pandemic distortions).

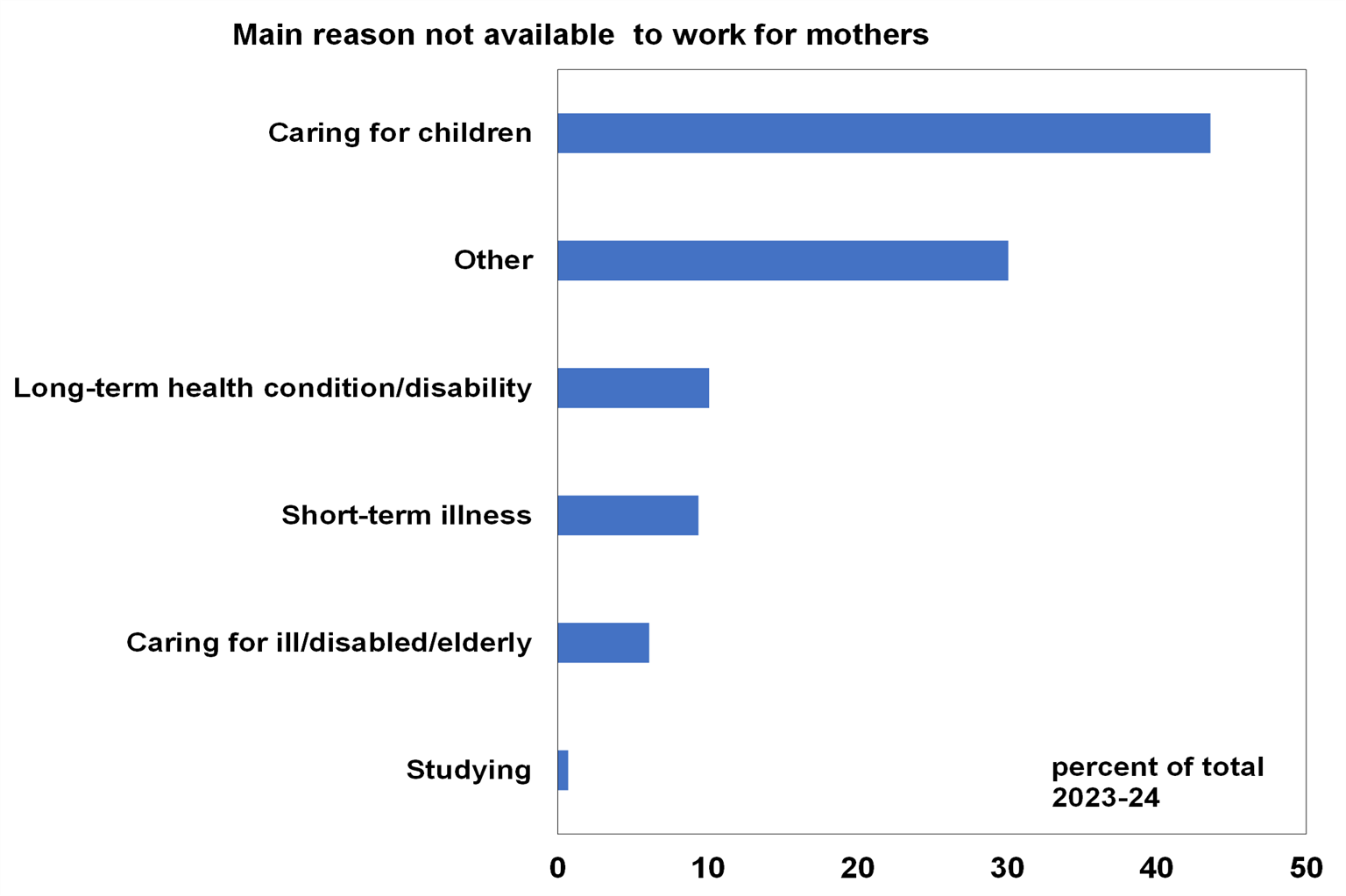

The main reason that women who wanted a job but were unavailable to work is is because they are caring for children (see the chart below) , which is the same as a year ago.

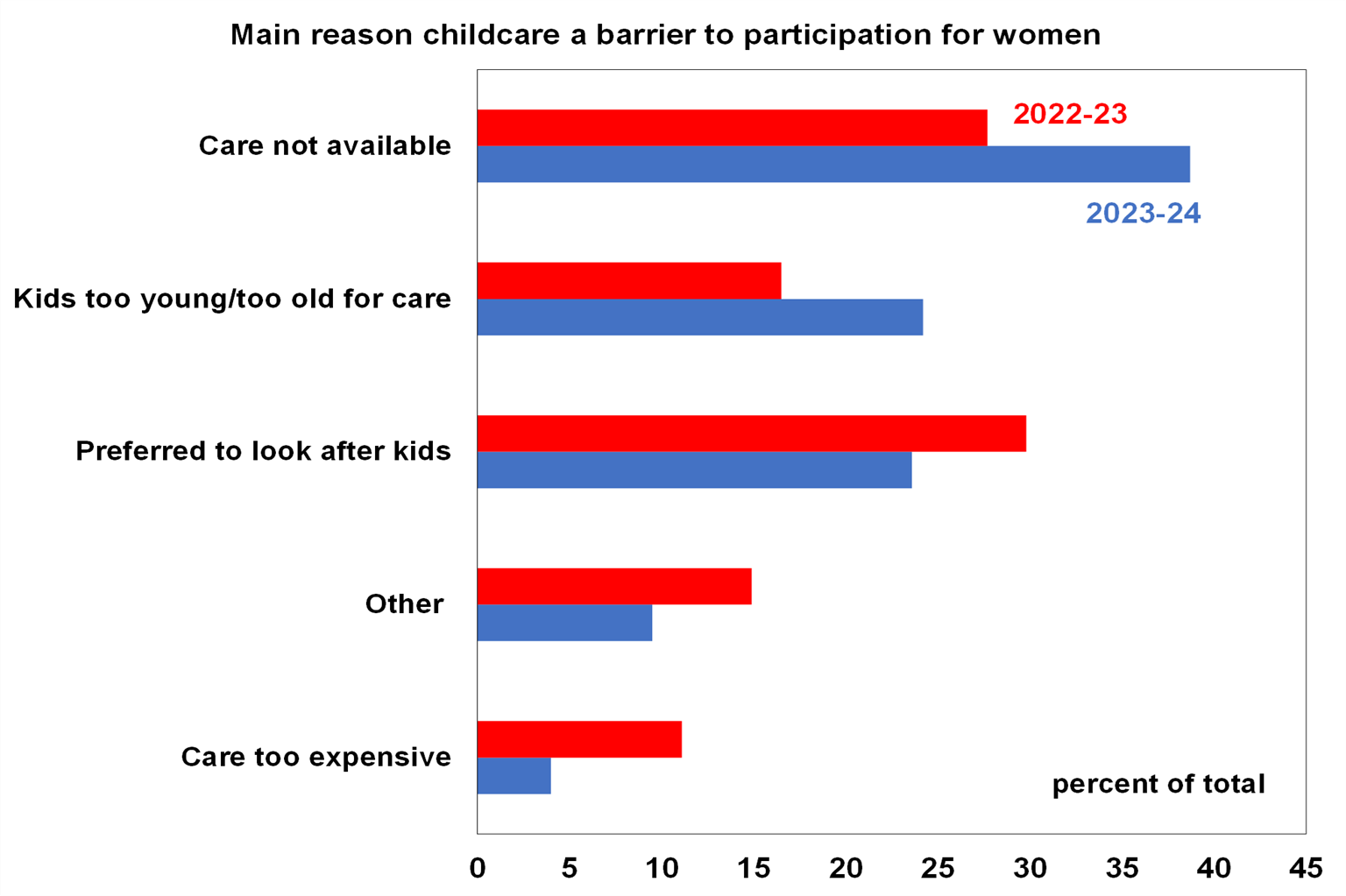

Of the females that said that childcare was the main barrier to workforce participation (and wanted a job), the main reason that it was an issue for them was because care was not available, followed by the kids being too young for care. This is a change compared to a year ago when the biggest barrier to labour force participation was women indicating that they preferred to look after kids. It was interesting to see that childcare being too expensive was now the least common reason as a barrier to participation. This is probably due to numerous government policies implemented in the Albanese government reducing childcare costs and activity tests required to access care.

The gender pay gap

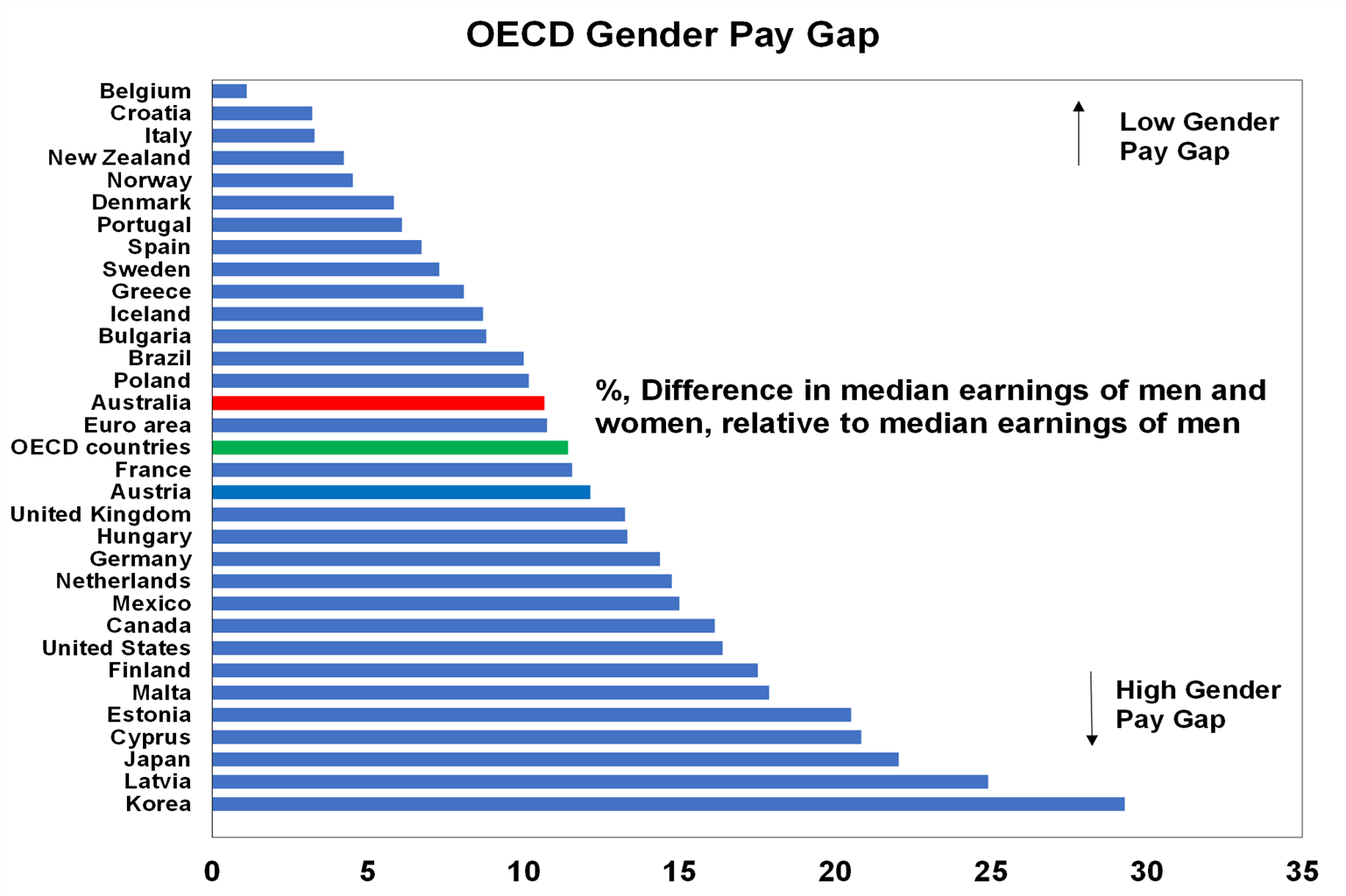

The gender pay gap refers to the difference in earnings from work for males and females for a full-time equivalent person. According to the OECD, there is an 11.5% difference in male and female pay across OECD countries (see the chart below) with Australia doing better than the average at 10.7%. Lower earnings in working life carries through to retirement and the impact gets compounded as balances grow. This is clear in the superannuation statistics, with the average female aged 60-64 having $300,717 in superannuation, which is 21% less than her male peer at $380,737.

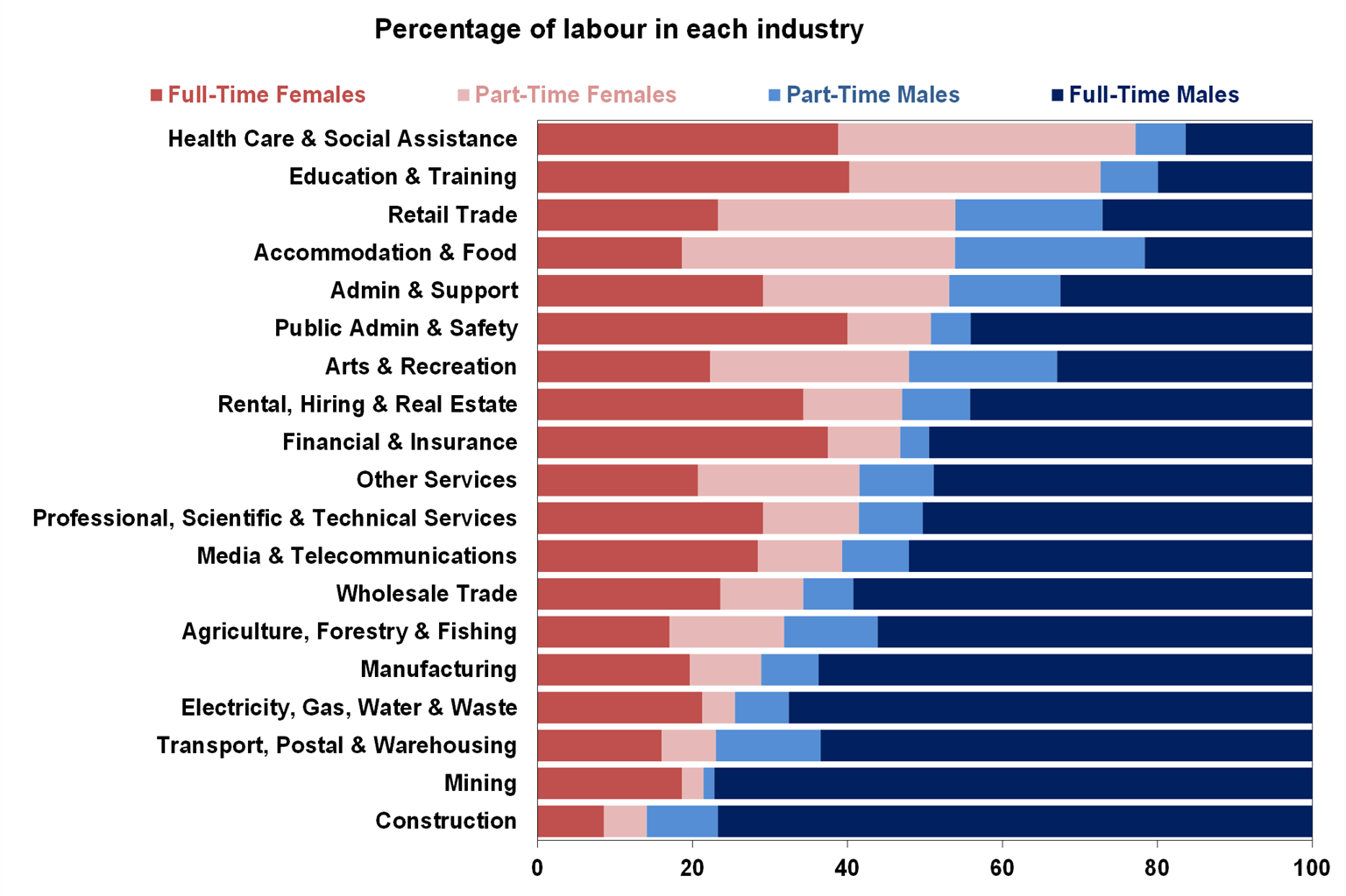

Unconscious gender biases in the workplace are still a big problem and need to be continually improved, but the other two main reasons for the difference in earnings between genders is the line of work undertaken and the decision to have children which takes time out of the workforce and can then result in a change of role or moving to part-time work. There is a significantly higher share of females in service-based industries (see the chart below) of health care and social assistance and education which are typically less lucrative, have higher flexibility around hours of work and require less travel requirements. While male dominance in manual industries like construction, mining, transport and postal, electricity, gas and water services and the manufacturing industries are typically paid higher rates because they are associated with less flexible hours and risky and manual work. There is probably also some societal bias that has typically placed less value on “softer” services skills.

Over the year to November 2024, the sectors that had the largest increase in employment were accomodation and food services, education and training and rental, hiring and real estate services. The sectors that had the largest falls in jobs were manufacturing, wholesale trade and arts and recreation services. So in the past year, women have benefitted from the growth in service-based jobs.

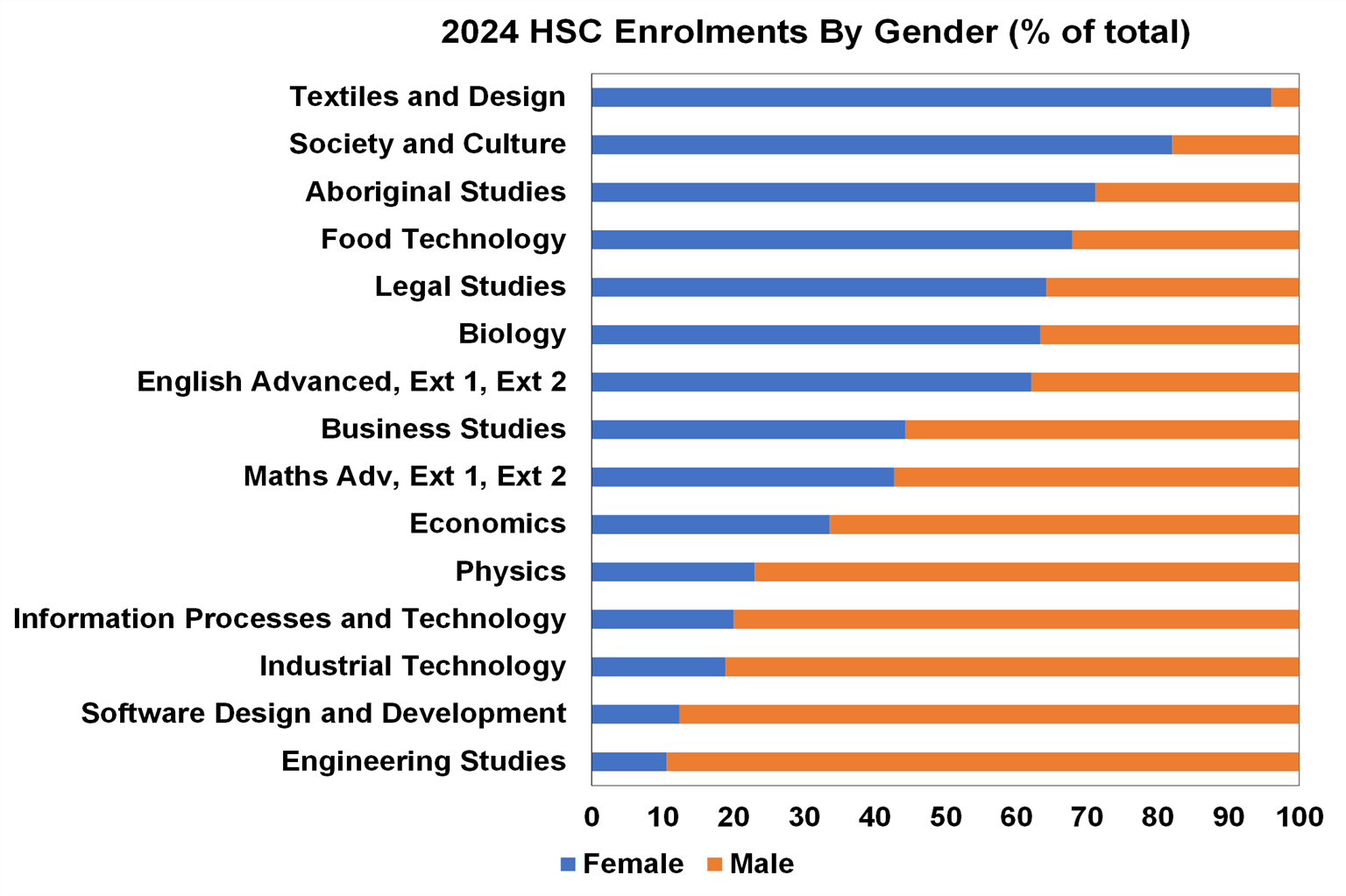

The difference in male and female job careers starts before the workplace. The chart below looks at HSC school enrollments in subjects with the biggest gender gaps. Females continue to dominate in subjects like textiles and design, society and culture, Aboriginal studies and food technology while males are still significantly dominating in engineering studies, software design and industrial technology. This was the same as a year ago. The drop in economics enrolments, especially for females has also been a longer-term trend and is concerning because of its impact on financial literacy.

What policies can help these issues

The changes from the Labor government to reduce childcare fees for families over the past year has been very encouraging. Paid parental leave policies in Australia are still not quite as generous compared to global peers that are having better results in reducing the gender pay gap (although its unclear if they will ever be as generous). There is also a case to look at further early childhood funding from the government (particuarly in the pre-school years). The countries that do the best on gender equality all have very generous parental leave schemes and universal access to early childcare. However, these policies argue for further spending which will be difficult in the near-term given recent legislation for the sector, constraints on further increases to government spending and concerns around stoking inflation from further government spending.

A more budget-friendly measure that can be achieved quicker would be to invest in improving female financial and economic literacy. We know that Australian female financial literacy is lagging behind males more than our global peers. This is occuring from a young age. There is a need for schools and families to expose girls and women to understanding the basics of investing and the implications that this on long-term returns through the impacts of compound interest. Teaching girls at a high school level the possible career pathways (and financial consequences) of the subjects that are taken at school is also important, especially in today’s world where tech is going to cause some change to how we work in the long-term.

From a societal point of view, there needs to be continued cultural change accepting fathers taking time off from work to look after the family, equally share the tasks of domestic unpaid work and encouraging a more holistic perspective on the work-life balance. The countries that tend to do the best in terms of gender equality and life balance are those with very generous welfare systems (that allow long leave periods) where equality within the family is ingrained in the culture.

You may also like

-

The outlook for Australian shares – is the long underperformance over? Australian shares have had a strong start to 2026 with the ASX 200 up 3.3% and flirting with a new record high. The local market has also outperformed US shares which are down 0.1% and global shares which are up 1.6%. However, this could just be noise and follows a significant underperformance against US and global shares since 2009. -

Weekly market update - 20-02-2026 Global share markets mostly rose over the last week. Worries about AI and tech valuations took a breather and the US Supreme Court decision to strike down Trump’s emergency power tariffs with Trump immediately announcing a replacement were seen as having little impact on the US growth outlook but were seen as positive for other countries. -

Econosights - An update on global debt and fiscal policy With the International Monetary Fund releasing their Global Fiscal Monitor recently, AMP's Senior Economist, Diana Mousina provides an update on the global debt situation and recent fiscal policy announcements.

Important information

Any advice and information is provided by AWM Services Pty Ltd ABN 15 139 353 496, AFSL No. 366121 (AWM Services) and is general in nature. It hasn’t taken your financial or personal circumstances into account. Taxation issues are complex. You should seek professional advice before deciding to act on any information in this article.

It’s important to consider your particular circumstances and read the relevant Product Disclosure Statement, Target Market Determination or Terms and Conditions, available from AMP at amp.com.au, or by calling 131 267, before deciding what’s right for you. The super coaching session is a super health check and is provided by AWM Services and is general advice only. It does not consider your personal circumstances.

You can read our Financial Services Guide online for information about our services, including the fees and other benefits that AMP companies and their representatives may receive in relation to products and services provided to you. You can also ask us for a hardcopy. All information on this website is subject to change without notice. AWM Services is part of the AMP group.